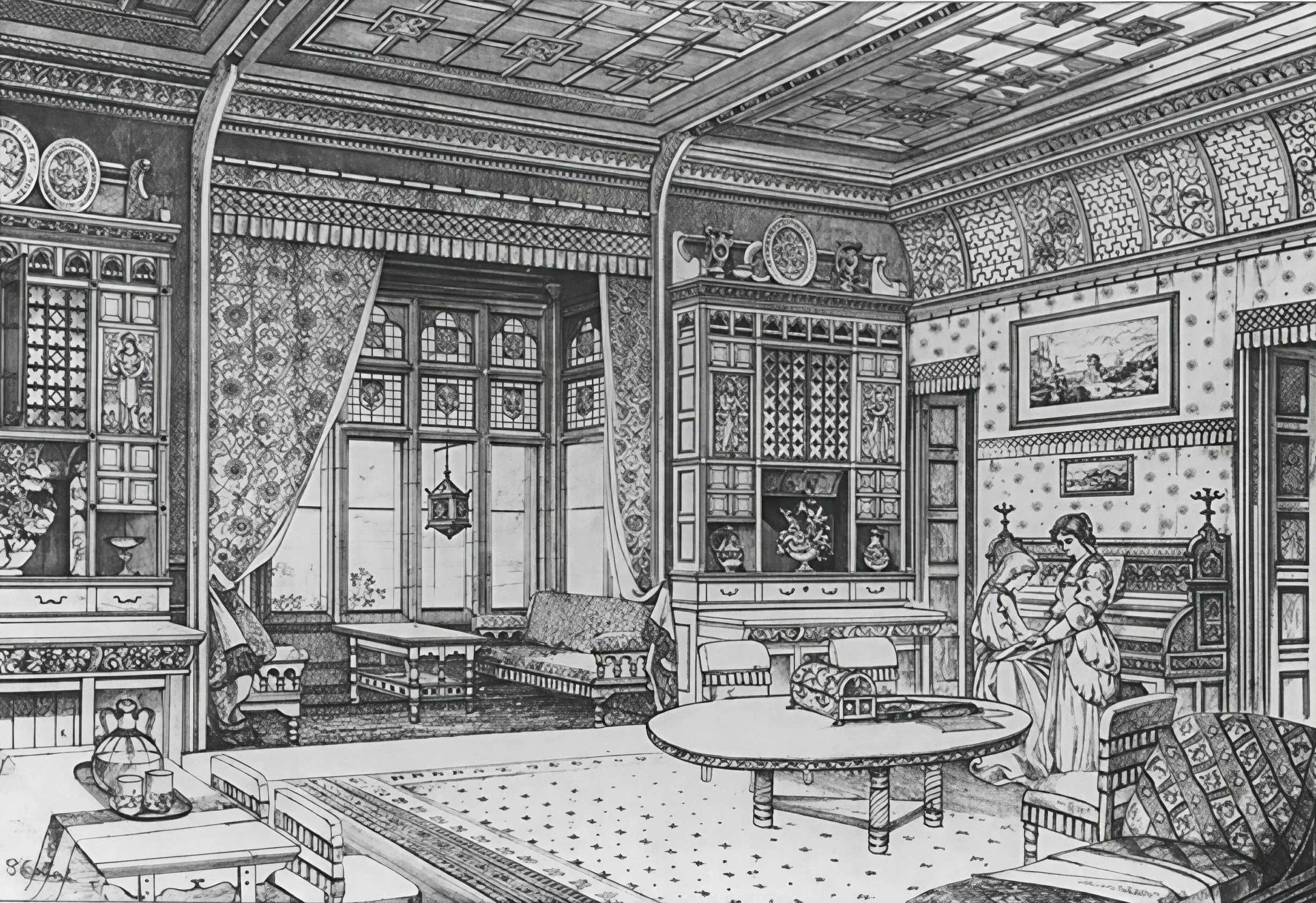

INTRO TO DESIGN REFORM: What is Design Reform and How Did It Start?

A Study of Decorations and Furniture. Bruce James Talbert. Illustration published in The Architect (magazine), July 24, 1869. Public Domain. PDM1.0 via Wiki Commons.

Every era of design history has wrestled with the tension between technological innovation and enduring human values. Long before the Industrial Revolution, critics debated whether innovations like Roman concrete or Renaissance perspective enriched or diminished art. But it was the “Machine Age” of the 19th century that pushed this tension to a breaking point. From this struggle emerged what we now call the Design Reform Movement.

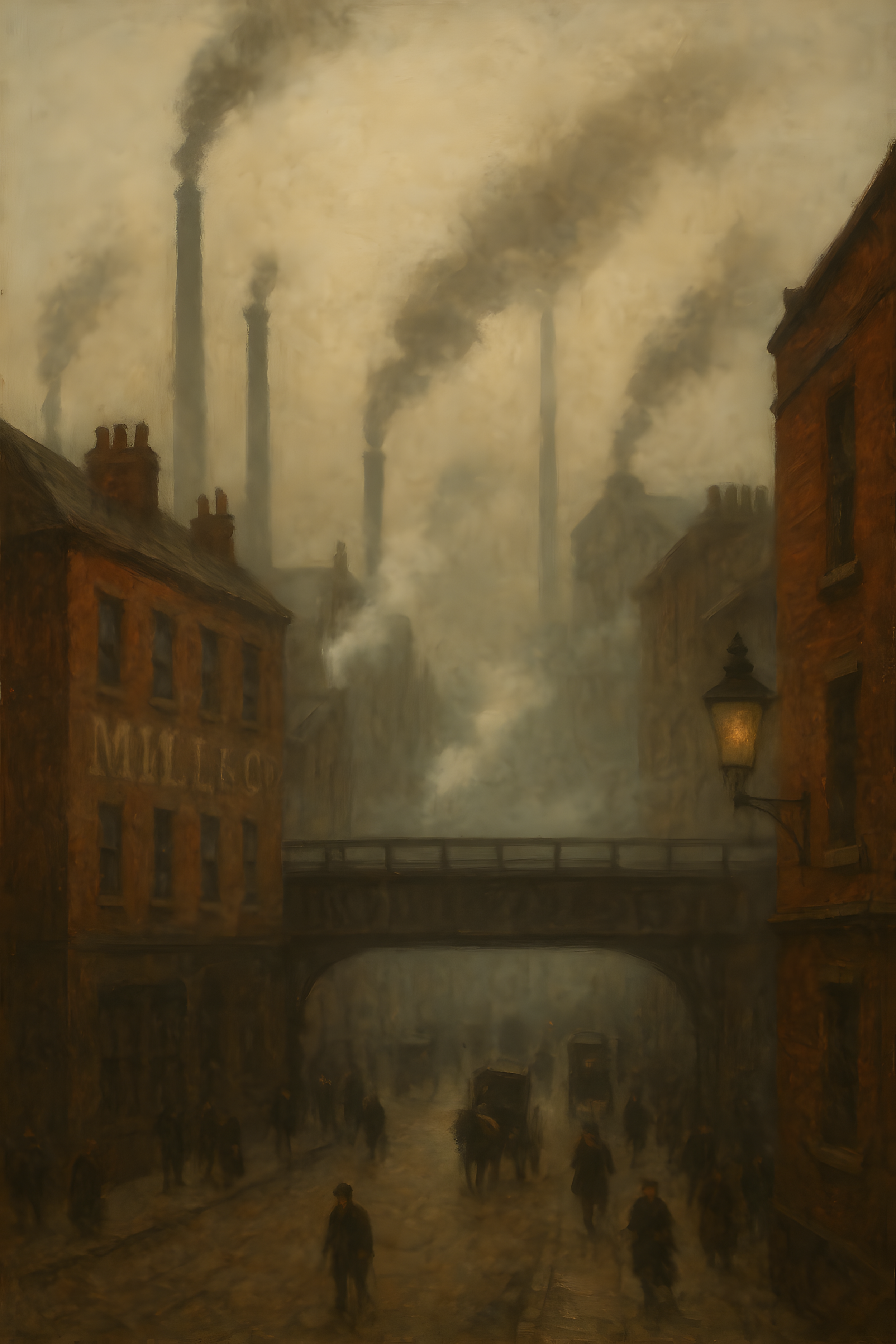

It began in England, birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, where its effects—both positive and negative—were felt most strongly. By the 1850s, industrialization had transformed the material world. Factories could churn out merchandise at unprecedented speed, volume, and low cost to satisfy the demands of the new middle class, which it had helped to create.

View of a nineteenth-century industrial town in England. AI-generated. Inspired by an actual scene. Teresa Ryan, 2025

What a typical advertisement for industrially produced furniture in nineteenth-century England would look like. AI-generated. Inspired by actual ads. Teresa Ryan, 2025

But what was gained in affordability was often lost in quality. Instead of hiring designers, manufacturers could simply pull ideas from the plethora of prints and pattern books generated since the advent of the printing press. Thus began the parade of Revival Styles -- Gothic Revival, Renaissance Revival, Rococo Revival, and more -- often poorly composed, made from inferior materials, and covered in superficial ornament. These mass-produced pieces—what most people think of today as ‘Victorian’ design—were often gaudy, derivative, and devoid of integrity. Critics argued that, beyond the lack of originality, these goods lacked harmony, proportion, and authenticity. They asked hard questions about honesty, beauty, and social responsibility.

To many critics, these objects reflected not progress but decline—a crisis of taste and values that demanded reform.

A pair of English, “Victorian”, Rococo Revival porcelain urns. c. 1835. Image courtesy of Liveauctioneers.com

Napoleon III center table. c. 1850. Image courtesy of Canonbury Antiques. canonburyantiques.com. The problems in Britain were the same in France, the United States, wherever industry had taken hold. And the issues were the same. While products of France might have been better quality than those of Britain, they were still 1) revival styles and 2) smothered in ornament.

Why these particular concerns?

Morality and the Victorian Lens

Honesty and authenticity: Structure was often concealed beneath cheap veneers or encrusted with “exotic” materials to appear more luxurious. An overabundance of machined ornament became a hallmark of the age. To Reformers, it was all smoke and mirrors—an illusion that concealed rather than revealed truth. In their words, it was a sham—a deception, untruthful, a ‘lie,’ and therefore immoral.

Beauty: A perennial and wide-ranging topic. But here, it was about the lack of sensitivity to “design” and “composition” -- which requires an understanding of the the Elements and Principles of Design. This was the heart of the problem with both FORM and ORNAMENT.

Beyond the visual, Reformers saw beauty as a moral force: uplifting, civilizing, and spiritually restorative.

Social Responsibility: The Industrial Revolution created various levels of wealth for many, but also unprecedented poverty for others. Families abandoned generations of farming, seeking greater financial security in factory jobs, but often faced long hours, low wages, and unsafe conditions. Society questioned the morality of this and advocated improving factory conditions. But Reformers deemed industrial production itself the problem on both moral and aesthetic grounds and argued, vociferously, for returning to hand-craftsmanship.

This tension -- embrace the machine and improve design and production techniques or revert to hand-made goods – lies at the heart of Design Reform.

A Victorian Family in a Drawing Room. Public Domain. Wiki commons. The Industrial Revolution created various levels of wealth for many.

AI-generated image, based on period photos. Teresa Ryan. 2025. For others, it created unprecedented poverty.

These intertwined concerns—honesty, beauty, and social responsibility—were all ultimately moral questions. In the Victorian mind, morality and aesthetics were inseparable. Morality, and beauty, and means/method of production were all woven together. Morality is so synonymous with the Victorian Age that the adjective “Victorian” itself has become shorthand for rigid, puritanical values. Reform logic ran like this:

• Nothing could be beautiful that was not truthful.

• Because truth is moral, so then is beauty.

• Products of industry, lacking truth and beauty, were immoral.

• Industrial production was also immoral due to both aesthetic failure and the exploitation of workers.

A Pragmatic View

Teapot. Christopher Dresser design for James Dixon & Sons, Sheffield, Britain. c. 1879. Public Domain. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Object no. 2021.152.2. Christopher Dresser spent four months in Japan on behalf of the government studying Japanese design with the goal of bringing a fresh perspective to British design.

That said, not everyone agreed that machines were the enemy. Government and industry leaders feared England was losing ground to France in the decorative arts. For them, the machine was here to stay — but design and conditions could be improved. The goal was not rejection but reform: better training, better products, better environments for workers.

As solutions were debated, one central principle emerged: the unity of the fine and decorative arts. Reformers argued that ehe same principles of proportion, beauty, and harmony that governed the fine arts — painting, sculpture, and architecture, — should also guide the decorative arts, the so-called “useful” arts—furniture, textiles, ceramics, glass, silver, and more. Since the Renaissance, the education of fine artists and craftsmen had followed separate paths. Now, it seemed, they must be reunited.

Enter the Aesthetic Movement

Liseuse. Georges Croegaert. 1888. Public Domain via Wiki Commons. Some Aesthetic design had a decidedly and intentionally hedonistic bent: exotic and hyper-sensual in terms of the variety of textures and materials and visual delights, all meant to induce physical pleasure. There was also often a casual, thrown-together, highly personal dimension to it.

The new emphasis on uniting the fine and decorative arts led, later in the century, to a movement that rejected both moralists and pragmatists: the Aesthetic Movement. This avant-garde group of artists and designers believed that art should not serve moral, industrial, or commercial purposes. Its only function was to give pleasure. Their motto: “Art for art’s sake.”

Three Main Paths of Design Reform

Moral/ Idealistic

Sussex Chair. William Morris

The Moral/ Idealistic Path looked backward. This hand-made, vernacular design symbolized simplicity, authenticity, and a more pure, pre-industrial, pre-capitalist, world.

Stylistic terminology:

Reform Gothic

Arts and Crafts

Image credit:

Sussex Chair. Designed by Philip Webb c. 1861, for Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co.

Ebonized beech.

Image courtesy of Live Auctioneers.

https://www.liveauctioneers.com/ item/164576936

Pragmatic

Side Chair. Christopher Dresser

The Pragmatic Path focused on the present. This machine-made, highly stylized version of the chair at left, infused with non-Western influence (Japanese), symbolized how industry could produce good design if guided by the right principles.

Stylistic Terminology:

None. Later absorbed into the Aesthetic category for its similar freedom of expression.

Image credit:

Side Chair. Designed by Christopher Dresser. Made by Chubb & Co., 1880-83. Ebonized mahogany, incised and gilt. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Accession no. W.35-1992

Aesthetic

Side Chair. Herter Brothers.

The Aesthetic Path claimed beauty simply for its own sake.

This elegant hybrid of machine and handwork epitomized “Art for Art’s sake.” Construction methods were irrelevant; beauty was the goal. Aesthetic designers were not moralists or reformers—they were artists of pleasure.

Stylistic Terminology: Aesthetic

Image credit:

Chair. Herter Brothers. c. 1878. Ebonized cherry, marquetry of lighter woods, gilding. Public Domain. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Object Number: 1992.80

Conclusion

While these approaches differed in philosophy and technique, they shared a common aspiration: to elevate design as an art form and to reconcile beauty with modern life. Reflecting a growing recognition—among designers and even segments of the public—that the reunification of the fine and decorative arts was the way forward, these new directions were collectively referred to at the time as “art furniture”—a term that captured not a single style, but a shared desire to rethink how objects were designed, made, and experienced.

Looking Ahead

Now that the groundwork is laid, we’ll turn next to Part I: The Moral/Idealistic Path—Pugin, Ruskin, Morris, and the Arts and Crafts Movement.

(or just click the arrow lower right)

Can you see -- or guess -- where this is heading?

Click here to download a free copy of The Three Main Paths of Design Reform, which includes more details.

Sign up below here to be notified about new posts -- and more.