DESIGN REFORM PART I: The Moral/Idealistic Path

Truth, Beauty, and the Arts and Crafts Movement in Victorian England

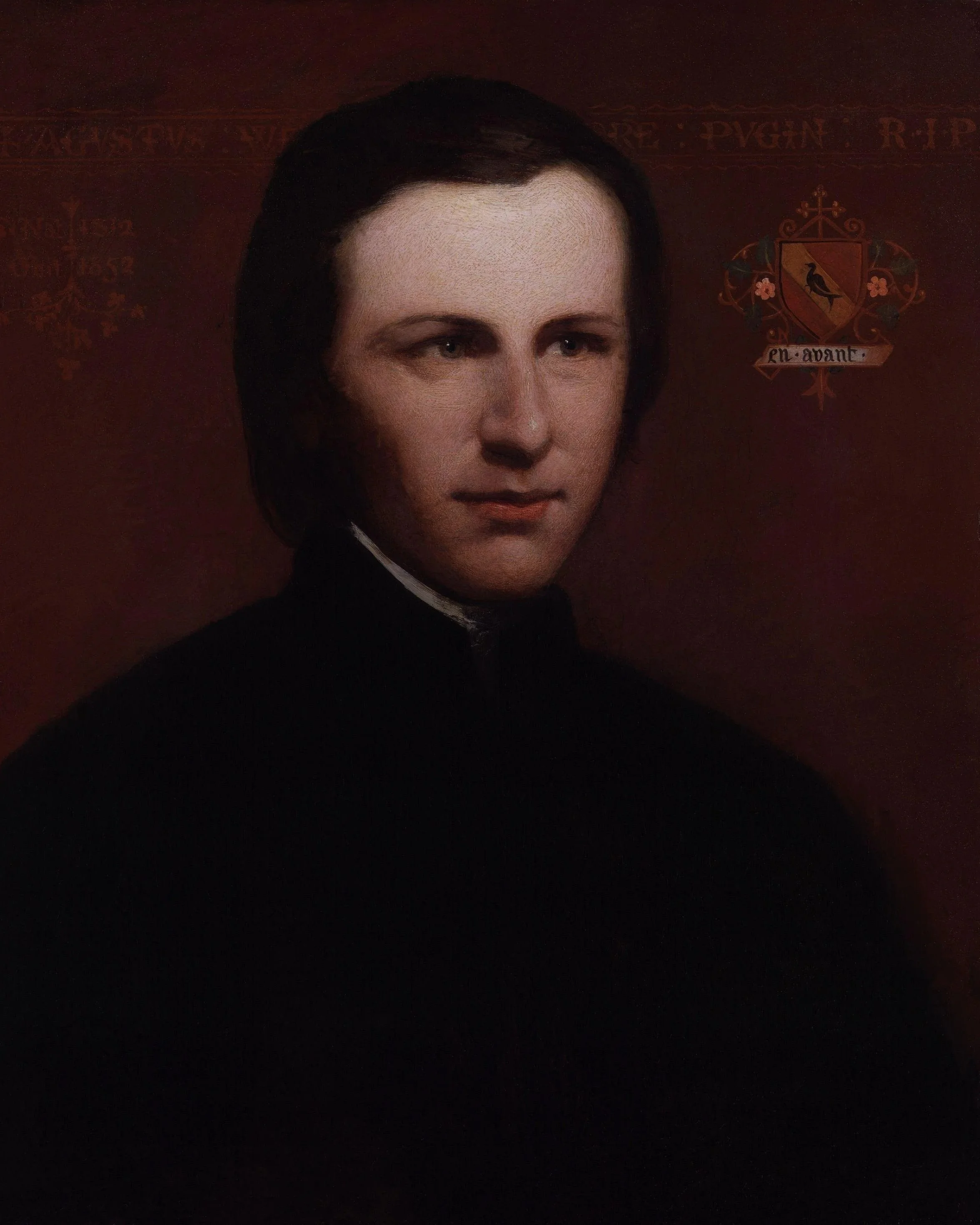

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-1852). Public Domain via Wiki Commons

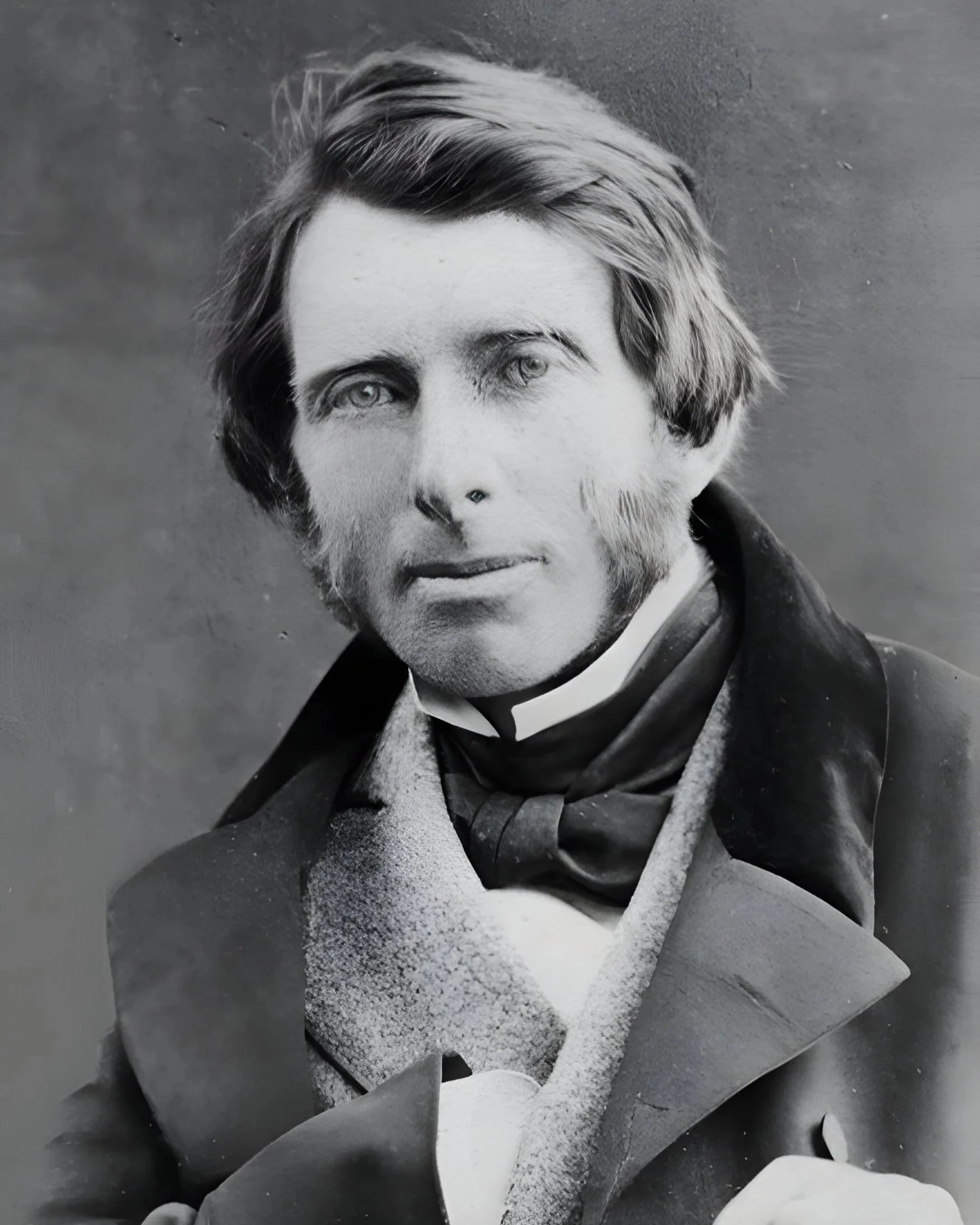

John Ruskin (1819-1900). 1863 W. & D. Downey. Public domain via Wiki Commons

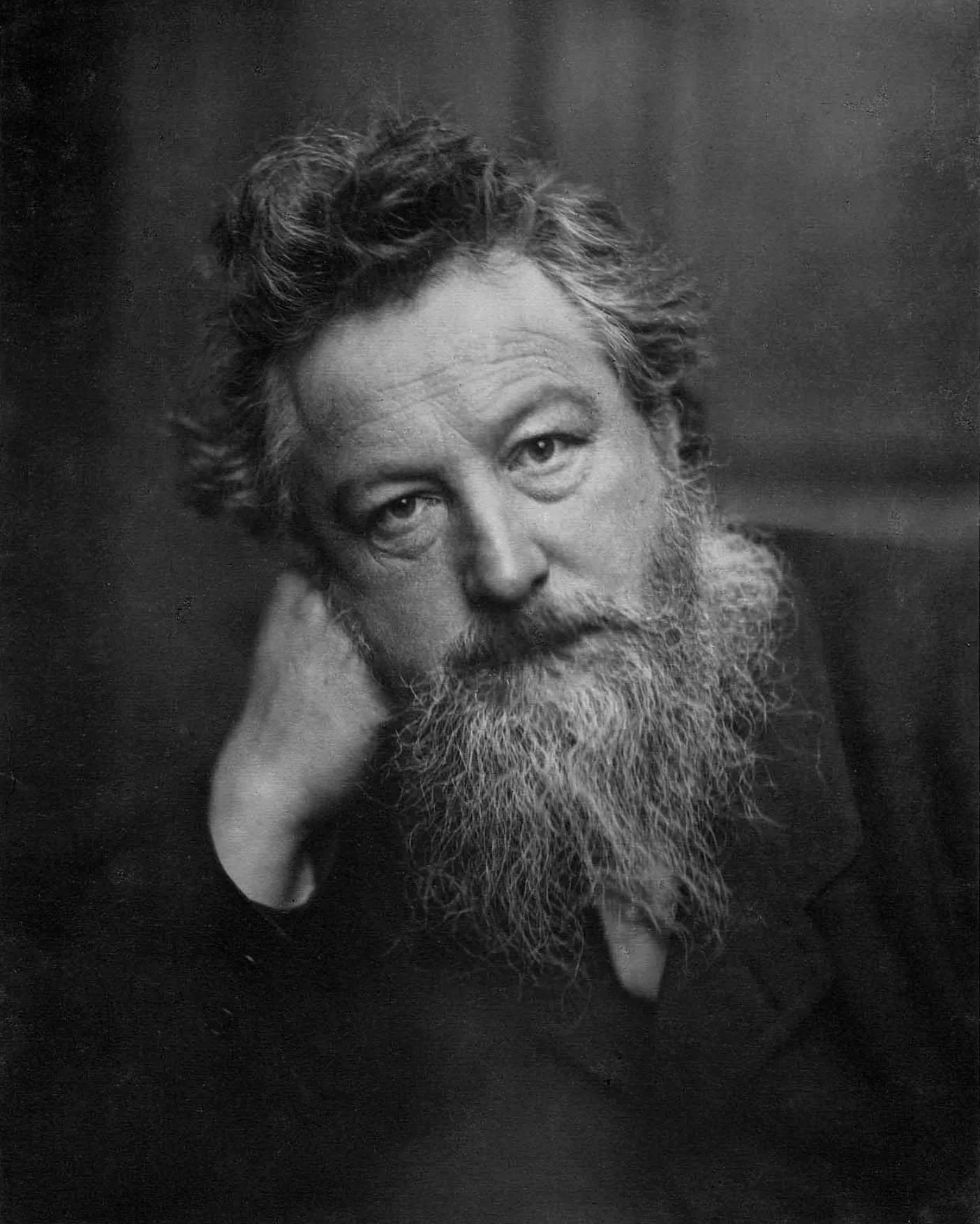

William Morris (1834-1896). Public Domain via Wiki Commons

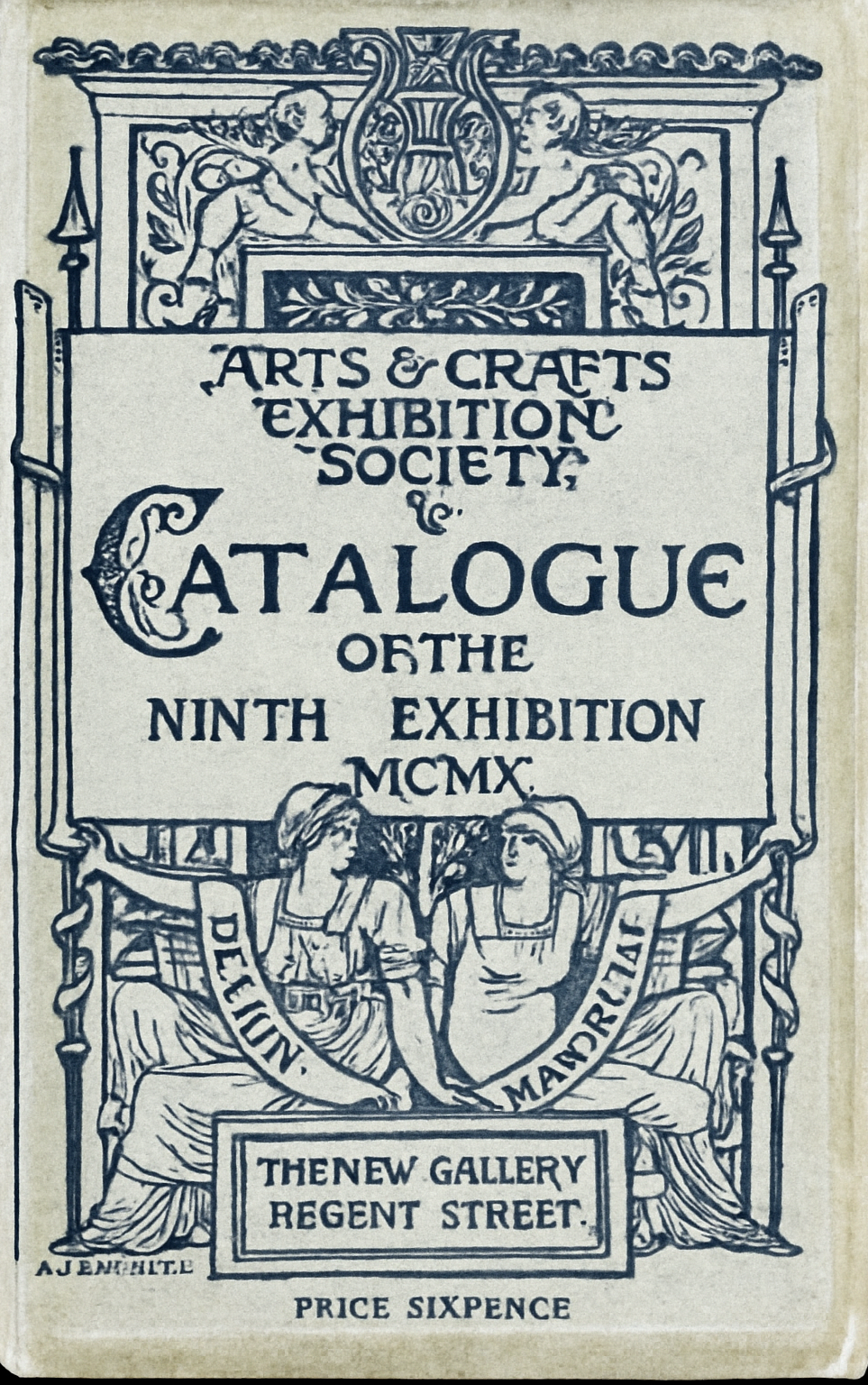

This Path of Design Reform was rooted in ideals of truth, honesty, and beauty. Its leaders—Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, John Ruskin, and William Morris—believed that design carried a moral weight. That the things people made and lived with could shape not only taste but also character, happiness, even society itself. It was upon this foundation that later followers of William Morris in particular founded the official Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society in 1887.

“We desired first of all to give opportunity to the designer and craftsman to exhibit their work to the public for its artistic interest and thus to assert the claims of decorative art and handicraft to attention equally with the painter of easel pictures, hitherto almost exclusively associated with the term art in the public mind. Ignoring the artificial distinction between Fine and Decorative art, we felt that the real distinction was what we conceived to be between good and bad art, or false and true taste ….”

Walter Crane. First director of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. Founded in 1887.

Catalogue cover for the Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society exhibition of 1910. Public Domain. Archive.org via Wiki Commons

Notice the emphasis here on equating the decorative arts with the fine arts.

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin was a man standing between two parallel design Paths --with a foot in each one. The first expressed the cultural shift from the reign of George IV to that of Queen Victoria — the “Family Values Queen” — who came to represent a return to moral restraint, domestic virtue, and social order. In contrast to the “pagan” Classicism of the previous generation — the gilded splendor and moral laxity of the late Georgian and Regency periods — the Gothic embodied faith, truth, decency, and humility.

When the Houses of Parliament conveniently burned down in 1834, the young Queen and her advisors seized the opportunity to declare the Gothic the national style of England. As a fervent Catholic convert, Pugin was completely aligned with this view, believing that the Gothic — the style of the Christian Church — was capable of restoring England to a proper moral way of life. The new Palace of Westminster became the quintessential expression of the Gothic Revival — in both architecture and interior design. The architect, Sir Charles Barry, was responsible for the plan and structure; Pugin, for the interiors, furniture, and much of the ornamental design.

Palace of Westminster. Sir Charles Barry. 1840-76. Public Domain via Wiki Commons

House of Lords, Palace of Westminster. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. 1835-52. Public Domain via Wiki Commons

The image below shows a piece of furniture by Pugin in what is known as the Gothic Revival style. The most striking feature is the “Gothic icing” — the overt symbolism: low-relief blind tracery, quatrefoils, the suggestion of pointed arches --that visually proclaim its ecclesiastical heritage. While for Pugin, this aesthetic carried profound spiritual meaning, for many others, it quickly became merely a fashion statement —the latest style. Period.

Even with all the ornament, this piece has more integrity than many “mainstream” Gothic Revival pieces.

1. The composition is balanced.

2. The ornament is “organized” by “compartmentalization.” It is not free-floating, but contained with geometric elements of the structure.

3. The ornament does not obscure the structure, but emphasizes it.

Compare this to the next image.

Armoire, designed in 1850 by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. Made by JG Crace. Public Domain. Victoria & Albert Museum. Accession no. 25:1 to 3-1852. Via Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0. This piece was made for the Gothic Court at the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition.

As mentioned in Intro to Design Reform, the challenges that concerned the Reformers were not limited to England. This spectacular example of French craftsmanship demonstrates the extraordinary skill and refinement of the period. Yet its exuberant surface ornament also reflects a prevailing nineteenth-century belief: that richness of decoration signified value. Reformers would work to redefine that idea, arguing that true worth lies in thoughtful design and structural integrity rather than in lavish embellishment alone.

Gothic Revival Dressoir. French, nineteenth-century. Image courtesy of Myers and Monroe. myersandmonroe.com

That this print predates the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster is evidence that, no matter how many styles came and went after the Middle Ages, the English never fully let go of the Gothic. Bits of it even crept into Renaissance design. By the late eighteenth century, it gained fresh impetus from the Romantic Movement, whose fascination with ruins, chivalry, and mystery made the Gothic — with its gargoyles, knights, dragons, and Arthurian legends — the perfect Romantic style. Though the prevailing taste of the time was Late Neoclassical, there were always those eager to go “full Gothic” —- or combine the two, as seen here.

An example of a fashionable Gothic Revival interior. After a drawing of Eaton Hall by John Chessell Buckler. 1826. Print by Charles Joseph Hullmandel. Published by William Clark. British Museum number 1944, 0704.50. Public Domain via Wiki Commons. While Gothic symbolism is paramount, the underlying furniture forms are pure Regency.

Even though his motivation had nothing to do with fashion, Pugin stood with one foot in the “mainstream” design world – from which all the Revival Styles will emanate – renowned as a major Gothic Revival designer. But because for him the Gothic represented morality, goodness, and therefore truth, honesty, and integrity, it should come as no surprise that he did not just have his foot in the second Path – he forged it.

For Pugin, good design was inseparable from moral integrity. Industrial shortcuts, false finishes, and sham ornament were not only dishonest but, in his view, sinful. While the symbolism of Gothic architecture never lost its meaning for him, in his search for honesty and humility, when designing for the average home, the elaborate ecclesiastical ornament gave way to a simpler, more restrained style, inspired by vernacular medieval craftsmanship.

This table is an excellent example of Pugin’s “other” style. It may fall under the broader category of Gothic Revival, but that label misses an important distinction. Here, Pugin is less concerned with Christian symbolism than with applying his own principles of good design — especially truth in materials and truth in construction (see sidebar). The emphasis on design reform that this piece embodies makes it something different: not Gothic Revival, but what is often referred to as Reform Gothic.

Table. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. c. 1852. Made by John Webb. Carved oak. Public Domain. The Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Accession number W.26-1972

This solid oak furniture, with its simple, visible joints and minimal applied ornament, embodied the humble authenticity that illustrated two of Pugin’s most important design tenets: truth in materials and truth in construction. These principles became the moral and aesthetic foundation of the entire Design Reform movement and led directly to William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement, where Gothic ideals were translated into a new, secular language of design integrity and social conscience. Their legacy is visible in the work of English designers such as Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, W. R. Lethaby, Ernest Gimson, and, in America, most famously in the furniture of Gustav Stickley.

Oak library table #636. Gustav Stickley. c. 1909. Image courtesy of Live Auctioneers. https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/11489623_a-gustav-stickley-oak-library-table-636-pasadena-ca

Design informed by the Middle Ages now splits in two directions: one decorative, symbolic — the “Gothic Revival,” inspired by the new Westminster, seen in ecclesiastical and fashionable interiors — and the other, a more honest, craft-based approach, sometimes referred to as Reform Gothic.

But Pugin’s moral certainty was only the beginning. It would fall to John Ruskin — poet, critic, and prophet — to transform these convictions into a philosophy: one that united art, labor, and the moral life into a single, inseparable whole.

Pugin’s Principles of Good Design

From The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture (1841)

Pugin’s basic reform principles have remained cornerstones of good design since their inception over 180 years ago.

“Now the severity of Christian architecture is opposed to all deception.”

Truth in Materials

“Construction itself should vary with the material employed.”

Materials must be used honestly and never disguised as something they are not.

Truth in Construction

“There should be no features… which are not necessary for convenience, construction, or propriety.”

Construction should be legible: one should be able to see how a building or object is put together and how each part supports the whole. This should not be hidden under ornament; no false joints or false structural elements.

Ornament Should Enrich Structure

“All ornament should consist of enrichment of the essential construction.”

Decoration must grow out of the form itself, not be applied superficially.

Ornament Should Be Appropriate

“In pure architecture, the smallest detail should have meaning or serve a purpose.”

Details must suit the use, material, and character of the design.

John Ruskin

If Pugin laid the foundation, John Ruskin (1819–1900) gave Design Reform its philosophy. In The Stones of Venice (1851–53), Ruskin argued that architecture reflects the society that creates it. For him, the decline of Venice was visible in its buildings—a lesson he applied to Victorian England.

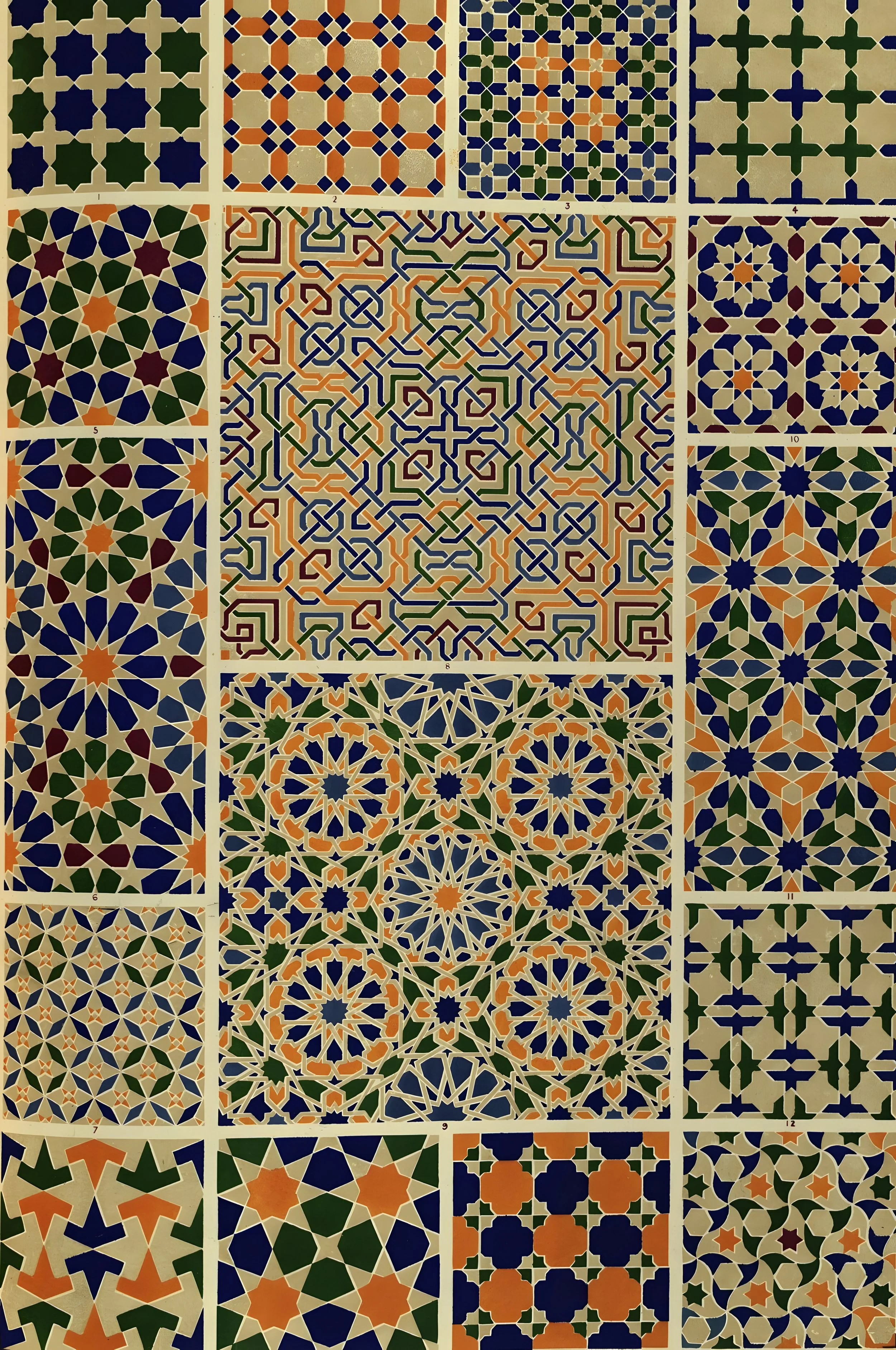

In particular, Ruskin admired Venetian Gothic for its fusion of Christian, Byzantine, and Islamic influences. The abstraction of natural forms in Islamic art resonated with his own ideals, as both traditions saw in nature a pathway to the Divine. For Ruskin, being “true to nature” did not mean copying leaves or flowers literally but observing the principles that governed their growth — structure, rhythm, proportion, and variation — and expressing those spiritual laws truthfully in design. The stylized geometry of Islamic ornament, far from denying nature, revealed its divine order through pattern and harmony.

In this shared search for order and moral integrity, Ruskin recognized a universal language of faith in design, one that transcended cultural boundaries and gave spiritual depth to the emerging philosophy of Design Reform. His openness to Middle Eastern design would prove especially influential, inspiring later reformers to look beyond Western models for patterns grounded in structure, abstraction, and the moral beauty of order.

Byzantine Ornament. Plate XXX from The Grammar of Ornament, by Owen Jones. 1856. Public Domain. Courtesy of The Cooper Hewitt Library.

Moresque Ornament. Plate LXIII from The Grammar of Ornament, by Owen Jones. 1856. Public Domain. Courtesy of The Cooper Hewitt Library.

Ruskin also brought a new point of view to handcraftsmanship through the lens of imperfection, which he saw as a virtue. The irregularities of Gothic carving revealed the freedom of the craftsman and the dignity of labor. Machine-made perfection, by contrast, stripped away humanity and reduced workers to servitude.

Green glazed jug. Fourteenth century England. Public Domain. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art object number: 2014.584

Industrially produced, identical jugs — machine-made perfection devoid of individuality. AI-generated image, inspired by originals. © Teresa Ryan, 2025

His critique of design expanded into a critique of society. Denouncing materialism, Ruskin believed that piles of possessions weren’t a sign of success but a symptom of moral decay. The Victorian passion for buying things, he warned, dulled both the eye and the spirit, burying beauty under clutter. Just as he argued that degraded labor conditions produced degraded merchandise — and that the ugliness of industrial products and the misery of industrial workers were inseparable -- he also believed that quality of character was inseparable from the quality of the products consumed. Beauty, he concluded, was not a luxury but a moral necessity.

Why Ruskin Admired Venetian Gothic

John Ruskin believed that Venetian Gothic represented the highest moral and artistic achievement of the Middle Ages. For him, it combined the most important qualities of good design:

A Union of Diverse Traditions

Venetian Gothic fused Christian, Byzantine, and Islamic influences — a visual proof that cultures could meet, exchange ideas, and elevate one another. Ruskin saw this openness as a sign of intellectual and moral vitality.

Honesty of Structure and Materials

He praised Venetian buildings for revealing how they were made:

clear structural forms

expressive tracery

materials used according to their nature

This transparency aligned perfectly with his belief in truth to materials and truth to construction.

A Deep Connection to Nature

Although Gothic ornament appears abstract, Ruskin argued that it expresses the laws and patterns of nature, not literal imitation. Its branching forms, rhythms, and variations reflected the organic principles he believed were divinely ordained.

Joyful Imperfection — the “Stamp of the Craftsman”

Venetian Gothic construction employed countless hand craftsmen, each contributing something slightly irregular and personal. Ruskin saw this as evidence of human dignity in labor:

“No good work can be perfect, and the demand for perfection is always a sign of a misunderstanding of the ends of art.”

For him, this imperfection was a moral and spiritual virtue.

A Model for Reform

Venetian Gothic embodied everything the Victorian mainstream had forgotten:

sincerity

vitality

respect for nature

a society in which labor and beauty were interconnected

It offered, in Ruskin’s view, a blueprint for restoring integrity to modern design.

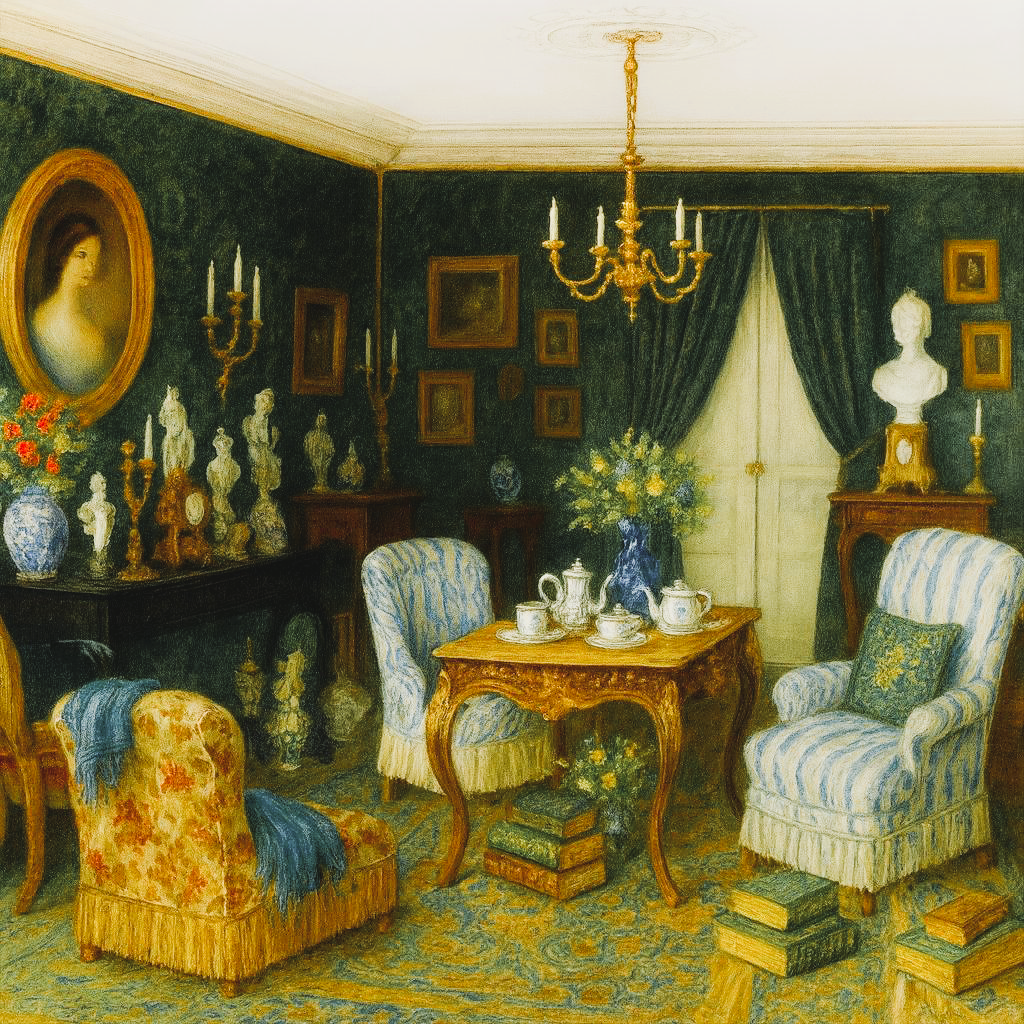

A typical Victorian “mainstream” (non-Reform) Interior. AI-generated, based on images of actual rooms.

@Teresa Ryan 2025

William Morris and the Practice of Reform

Textile. Strawberry Thief. Designed by William Morris. 1883. Public Domain. Courtesy of the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. Accession no. 1935-23-21

If Pugin laid the foundation and Ruskin supplied the philosophy, William Morris (1834–1896) carried Design Reform into lived practice. More than any other figure, Morris gave tangible form to the ideals of honesty, beauty, and integrity. He was not only a theorist but also a craftsman, designer, entrepreneur, and activist.

Morris began as a devoted reader of Ruskin, absorbing the call for truth to nature, respect for materials, the dignity of labor, and the significance of beauty. But where Ruskin remained a critic, Morris turned ideas into objects. He founded workshops that produced furniture, textiles, wallpapers, books, and stained glass — all rooted in handcraftsmanship and natural beauty.

Detail from The Charge of David to Solomon in Trinity Church, Boston. 1882. Stained glass. By Edward Burne-Jones and Morris & Co. Public Domain via Wiki Commons. Naturally, as an avowed Medievalist, one of the crafts Morris is most renowned for is stained glass.

For Morris, the flood of cheap, imitative goods degraded both taste and life. His solution was to turn back to what he saw as a purer age — before the machine, before capitalism — to the Middle Ages. Yet unlike the Gothic Revivalists, he did not copy medieval forms literally. He absorbed their spirit and structure, abstracting and stylizing motifs into rhythmic, contemporary patterns. This approach — drawing from the past but reshaping it for the present -- a truly fine line to tread— became a defining characteristic of Design Reform.

That said, as a devout Medievalist, Morris’s work does not obscure the source of inspiration, which meant so much to him personally. It often looks “Gothic,” and is sometimes labeled “Gothic Revival;” yet it belongs more rightly to the Reform Gothic tradition. His goal wasn’t to replicate the past, but to renew it. When we look closely, and because we know his intentions, we see that he avoided mere imitation: beneath the surface, the principles of the Reformers are at work — truth in materials, integrity in design, and beauty rooted in moral purpose rather than style alone.

Medieval Court Cupboad. Oak. European. 16th century. Image courtesy of Fontain’s Auction https://www.fontainesauction.com/auction-lot/16th-century-gothic-oak-court-cupboard_61647DBA29

While the above cupboard displays many characteristics of Gothic design — low-relief, organic ornament; slender colonnettes at the corners with religious figures; biblical scenes; and the shaped base, the horizontal emphasis of the structure; the geometry of the panels; and the solidity of the figure in the central panel all point to the influence of the Italian Renaissance style which, by the 16th century, was well-known throughout Europe. Interestingly, Morris’ ornamental views are often based on the style of imagery common to the so-called Courtly style — the elegant, affluent style that appeared at the end of the Middle Ages, on the threshold of the Renaissance — similar to that on his cabinet at right, which is an interesting, transitional piece, between the Gothic and Renaissance.

Backgammon Players. Philip Webb, Sir Edward Burn-Jones for Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. 1861. Public Domain. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Object no. 26.54.

This cabinet is of the Reform Gothic type, known at the time as “Modern Gothic” or “art furniture.” It evokes the spirit of the Middle Ages without resorting to the literal vocabulary or imitation of Gothic architecture. The imagery recalls that on the original cabinet and, with its richness of pattern and color, also points to medieval tapestries and illuminated manuscripts. Yet the ornament serves to articulate the simple, legible structure it adorns—box, shelf, and posts—clearly expressing the Reformers’ principle of truth in construction. The flat, two-dimensional painted panels by Sir Edward Burne-Jones adhere to the same standards, epitomizing the Reform aim of reuniting the fine and decorative arts.

Morris believed that beauty and function should be inseparable in daily life. As he famously declared in The Beauty of Life (1880), “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” This was more than advice on home decoration — it was a moral philosophy. He saw everyday surroundings as a reflection of one’s values, and the making of beautiful, useful things as a way to restore integrity to work and joy to living. In uniting usefulness with beauty, Morris brought the moral ideals of the Reformers into the heart of the home.

For Morris, beauty was not a luxury but a necessity. His dream of making beautiful, handcrafted goods affordable to all was deeply idealistic, rooted in a belief that art could elevate life and labor alike. His admiration for the communal spirit of the medieval craftsman gave rise to the idealism and utopian socialism at the heart of his enterprise — a vision in which art, work, and society might once again form a single, harmonious whole.

Through Morris & Co., he built a commercial enterprise that trained craftsmen, revived traditional techniques, and spread the Reform ethos. Ideally placed to fulfill the Reformers’ call to unite the fine and decorative arts, Morris drew on his Oxford circle of friends — including members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Reformers in the fine arts who were supported by Ruskin. As seen in The Backgammon Players just discussed, several contributed designs for merchandise and interiors produced by his firm, in some cases even participating in their creation.

The Beguiling of Merlin. Edward Burne-Jones. 1874. Lady Lever Art Gallery. Public Domain via Wiki Commons

The Day Dream. Dante Gabriel Rossetti. 1880. Victoria & Albert Museum, Accession no. CAI. 3. Public Domain via Wiki Commons.

Burne-Jones and Rossetti were members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of artists rebelling against the strict conventions of academic painting — just as the Design Reformers were challenging those of furniture and interior design. As friends of William Morris, whom they met at Oxford, it was only natural that they would join him in his effort to reunite the fine and decorative arts when he opened his firm. Interesting aside: The Day Dream model was Rossetti’s muse and lover of ten years — who also happened to be William Morris’s wife, Jane — with his full knowledge of the affair. So much for Victorian morality! Even among the “moral” group.

Pair of Rush-Seated Armchairs. Dante Gabriel Rossetti for Morris & Co. c. 1880. Image courtesy of Puritan Values. https://www.puritanvalues.com/product/dante-rossetti-for-morris-and-co-a-pair-of-morris-and-co-rush-seated-armchair. While the rush seats and turned elements evoke the vernacular, the ebonized frame and elegant lines point to the influence of Japan. Both mark these chairs unmistakably as Reform.

Buffet. Philip Webb. c. 1880. Black lacquered and partially painted and gilded mahogany. Leather repoussé, painted, and gilded. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons 3 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pour_morris_%26_co.,_philip_webb,_buffet,_londra_1880_ca.,_01.JPG. Musee d’Orsay.Object no: OAO 449. The image has been edited for clarity. Background removed. Shadows removed. Color and contrast adjusted. Repoussé and painted or gilded leather was often used as wall covering in the late Middle Ages. Here, the technique is applied to a contemporary piece of furniture. The colorful, two-dimensional patterns recall the brilliance of medieval tapestries and illuminated manuscripts. Such artistic and hand-craft–based treatments would never appear on standard, factory-produced Gothic Revival furniture. Combined with the black lacquer finish, these features identify the piece unmistakably as Reform Gothic.

Red House

Morris’s ideals found their clearest architectural expression in his own home, Red House (1859), designed with Philip Webb. Built of local brick, with exposed structure and handcrafted detail, it embodied the Reform principles of truth, unity, simplicity, and authenticity. In the manner of English medieval castles and manor houses, the plan is a massing of volumes arranged organically around use rather than symmetry. Yet in the Reform spirit, the structural forms are stylized and stripped of the “medieval” ornament that would have made the house feel like a revival. (See link to Red House at end of article).

Red House, Bexleyheath. Greater London. Philip Webb in consultation with William Morris. 1859-60. Photo by Ethan Doyle White. Public Domain via Wiki Commons. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ Color adjusted for editorial purposes.

The organic clustering of forms recalls Compton Wynyates, yet the medieval details are intentionally stripped away. By reducing the design to simple, legible volumes, Reform architects could build on meaningful historical models while avoiding imitation and establishing a new, contemporary architectural language. (For more on Red House – the interiors and furniture – see the link at the end of this article, or click here)

Compton Wynyates Manor House.Warwickshire, England (c.1480–1520). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Compton Wynyates represents the classic English manor house. Note that “classic” means “quintessential,” not classic-al architecture, for its irregular, asymmetrical massing stands in direct contrast to Classicism. That very departure — combined with its authenticity as an indigenous English form — made it a key precedent for Reform architects and designers.

What “handmade” meant to William Morris

For William Morris, hand-made meant far more than craft in the workshop. It included:

• Growing plants to produce natural dyes

• Preparing and mixing the dyes

• Raising sheep for wool

• Carding and spinning the wool

• Finally weaving and finishing the rug or textile

This new honesty — a cluster of simple, functional, geometric forms — proved profoundly influential, shaping not only the language of the Arts and Crafts movement but, decades later, the domestic architecture of early Modernists from Voysey, to Frank Lloyd Wright, to the Bauhaus Masters’ Houses. What began as moral honesty in materials became structural honesty in form.

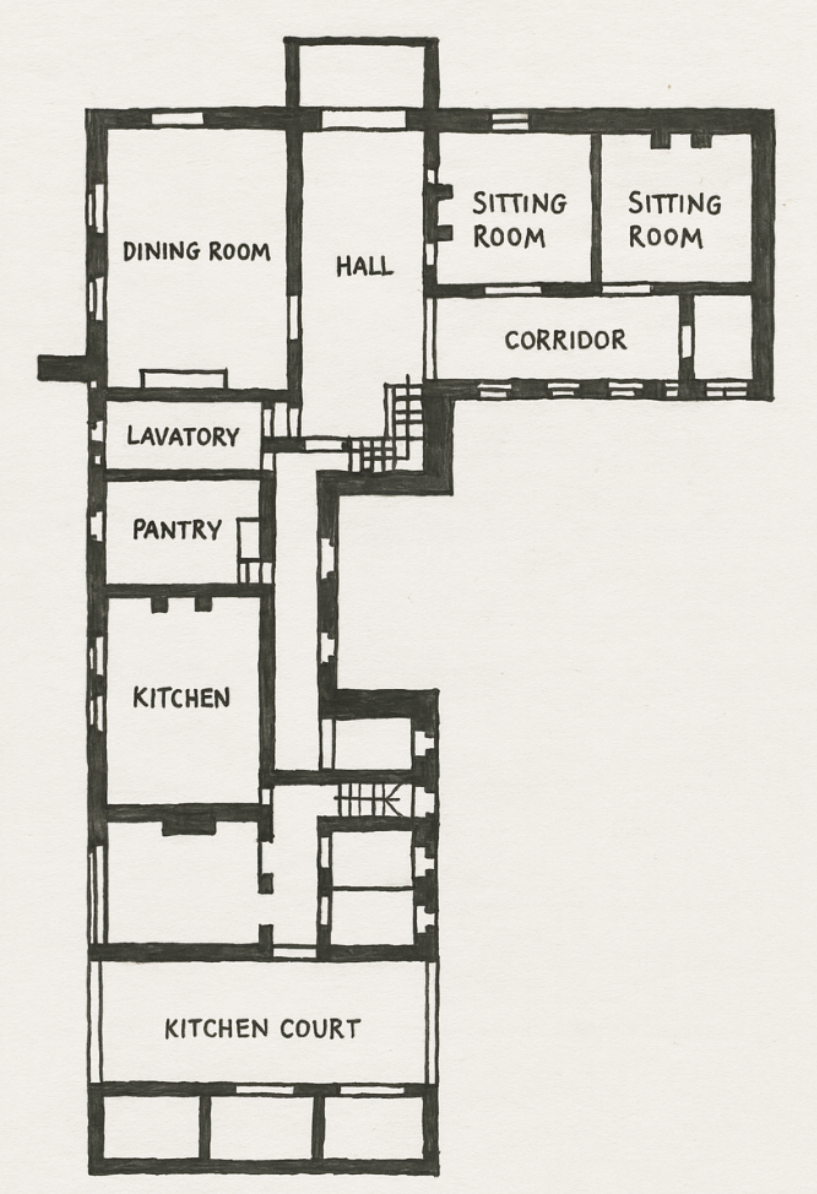

Ground floor plan of Red House, Bexleyheath. Philip Webb in consultation with William Morris. 1859-60. AI-generated @TeresaRyan, 2025

CONCLUSION

Thus the Moral/Idealistic Path of Design Reform—from Pugin’s religious honesty, to Ruskin’s ethical aesthetics, to Morris’s union of beauty and labor—did more than revive medieval principles. It reshaped the very foundation of design. What began as a plea for truth in materials and construction became a new way of conceiving form. What began as a protest against industrial injustice evolved into a vision of design as a moral force. And that vision culminated, generations later, in the clarity of Early Modernism.

Yet this was only one of the forces reshaping Victorian design. Running parallel to it was a second, equally influential current—grounded not in morality or medievalism, but in pragmatism. Its goal was to improve the quality of industrial production, strengthen competitiveness, and systematize the training of taste. This movement began not in workshops or guild halls, but in classrooms, museums, and schools of design.

Together, these two Paths—the Idealistic and the Pragmatic—reshaped the values of an entire age and laid the groundwork for everything that followed in Design Reform.

For further reading: Intro to Design Reform

For further information: There is so much to know and enjoy about William Morris and his work. Here are just a two links to help you explore:

https://williammorrissociety.org/

https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/place/red-house

Click here to download Pugin’s Principles for Good Design

Sign up below to be notified about new posts…and more.