Design Reform Part II: The Pragmatic Path Government and Industry

The Crystal Palace, South Kensington, and the Education of Taste

If Pugin, Ruskin, and Morris carried the Moral/Idealistic torch of Design Reform and sought the solution in the past, the Pragmatic Path belonged to government officials, educators, and industrial advisors, whose focus was squarely in the present. Their goal was practical: improve manufacturing standards, refine public taste, and build institutions that could disseminate the principles of good design….all of which would help them compete more successfully in a rapidly expanding world market.

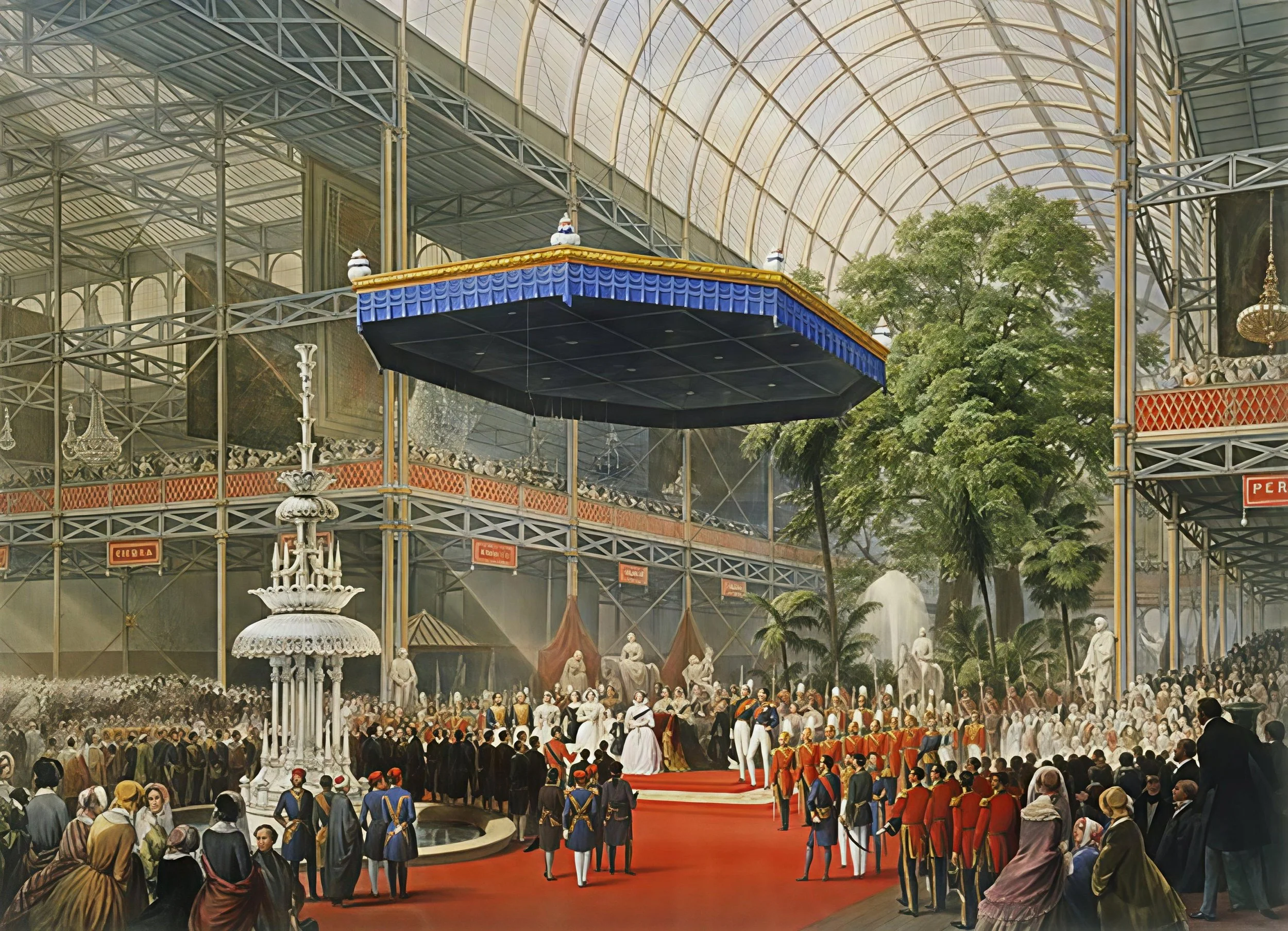

The Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Read & Co. Engravers & Printers. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. The event and the structure that symbolized Victorian industrial power and the crisis of taste that launched design reform.

The Great Exhibition and the Crystal Palace

The Great Exhibition of 1851, organized by Prince Albert and Henry Cole, was housed in Joseph Paxton’s spectacular Crystal Palace. It brought together 100,000 objects from across the globe and showcased both the triumphs and failings of British industry. Engineering was impressive, but manufactured goods—furniture, textiles, metalwork—were often smothered in meaningless ornament or weighed down by clumsy historical imitation. (See Intro to Design Reform and Design Reform Part I.)

To reformers, the Exhibition confirmed what they already suspected: industrial Britain faced a crisis of taste, and a transformation was urgently needed.

Queen Victoria opens the Great Exhibition. Louis Haghe, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Pugin’s Exhibition at the Fair

At the Great Exhibition of 1851, A.W.N. Pugin used his display to teach lessons in design integrity, by presenting a range of objects that embodied his core principles around truth and authenticity. While Pugin was a prolific designer of wallpaper, we do not know for sure whether or not he included wallpaper in this exhibit. However, Victorian wallpaper affords an excellent opportunity to illustrate a core principle of Pugin’s and other design reformers.

Much of the mass-produced, “mainstream” wallpaper of the period expressed the most recurrent and fundamental problem: applying three-dimensional, illusory imagery to a flat, two-dimensional surface, bearing no structural relationship to the paper or the wall beneath. To Pugin, this was a violation of truthfulness on more than one level. It was not merely poor taste; it was a visual lie.

Below: By comparing a Pugin wallpaper, grounded in clear geometry, flat pattern, and structural logic, to a particularly faulty, mainstream design, the contrast he would have wanted the public to understand is clear.

For further interest, a later example by William Morris is shown as well. While infused with a feeling of “naturalism,” Morris’ papers respect the “reality” of the flat surface.

A “mainstream” Victorian wallpaper. From The Sutton-Pierson House – 31 Washington Street, Peabody MAPeabody Historical Society and Museum

Gothic Lily Wallpaper. Designer A.W.N. Pugin. Manufacturer: Woollam & Co. Of London, c. 1850. Courtesy of Chairish/ 1st dibs

Pink and Rose Block-printed wallpaper. Designer William Morris c.1890. Manufacturer: Morris & Co. Printer: Jeffrey & Co. Public Domain courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Object no: 23.163.4a

Henry Cole and the Wellspring Vase Family

At the center of these efforts was Henry Cole (1808–1882), civil servant, educator, and tireless advocate of design reform. Cole believed that good design was a matter of education — for both industry and the public. He collaborated with Richard Redgrave, painter, designer, and inspector of design schools, on works that embodied reform ideals. One of the clearest examples was the Wellspring Vase, of 1847.

Wellspring Carafe. Designed by Richard Redgrave. 1847. Commissioned by Henry Cole. Made by John Fell Christy, Stangate Glass Works. Lambeth, England, active 1840/50. Public Domain. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Victorian Bristol glass ruffle vase. One of a pair. Courtesy of Tailors Treasure Store https://www.etsy.com/listing/1756671139/victorian-ruffled-edge-bristol-glass

This “mainstream” Victorian Bristol glass vase has been completely covered in paint, obscuring the basic material, so looking more like a ceramic than glass. And the scene depicted, while charming and somewhat following the form of the vessel, is more suitable for an easel picture than a vase. So too much “inappropriateness” for design reformers.

Fine Art Meets Decorative Art

Redgrave’s background as a fine artist shaped his approach to form and ornament:

• A thoughtful balance between empty and ornamented space. Just enough ornament to convey meaning.

• The base material – glass -- is apparent and part of the design.

• The ornament enhances the form and accentuates the shape rather than obscuring or distracting from it.

• The stylized, two-dimensional ornament respects the flat surface.

• The ornament is rationally placed at the bottom, sitting in the water.

• The ornament is “meaningful.” That is, directly related to the vessel’s function.

For Cole, this was precisely the point: ornament should be artistic, meaningful, and in harmony with purpose and the Elements and Principles of Design. By comparison, many popular Victorian products, such as painted Bristol glass vases, obscured their materials and treated surfaces as canvases for picture-making—exactly the “inappropriateness” reformers fought against.

The South Kensington System

Fromthe Crystal Palace Exhibition came the Department of Science and Art and the South Kensington Museum (today’s Victoria and Albert Museum). Under Cole’s leadership, these institutions supplied schools with casts and pattern books, trained designers, and exposed the public to approved examples of good taste. This structured approach became known as the South Kensington system.

The South Kensington approach emphasized:

• Copying approved models

• Mastering geometry and proportion

• Studying ornament across many cultures

The emphasis on form, proportion, and geometry reflected a desire to give decorative artists something of the rigorous foundations taught in the academies of London, Paris, and Rome. While critics such as Ruskin condemned its rigidity, arguing it produced mechanical minds rather than creative ones, it nevertheless shaped design education across Britain and its empire for decades and produced tangible benefits.

It standardized design instruction across Britain, strengthened regional schools, and provided industry with designers who were better trained in proportion, form, and ornament. Though the system did not achieve the sweeping transformation its founders envisioned, it played an important role in elevating the general level of industrial design.

The South Kensington approach to design education emphasized:

• Copying approved examples (plaster casts, pattern books)

• Learning geometry and proportion

• Studying ornament from many cultures

AI-generated based on what the studios actually looked like. @ Teresa Ryan 2025

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London is the oldest and largest museum in the world dedicated to design and the decorative arts. Founded in 1852 as the “Museum of Manufactures,” it was the direct governmental response to the poor quality of industrial design revealed at the Great Exhibition.

The Victoria and Albert Museum. North side of Garden, by Captain Francis Fowke, Royal Engineers, 1864–1869. (color has been lightened for editorial purposes) Public Domain via Wikipedia https://www.flickr.com/photos/16564965@N04/52023540671/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

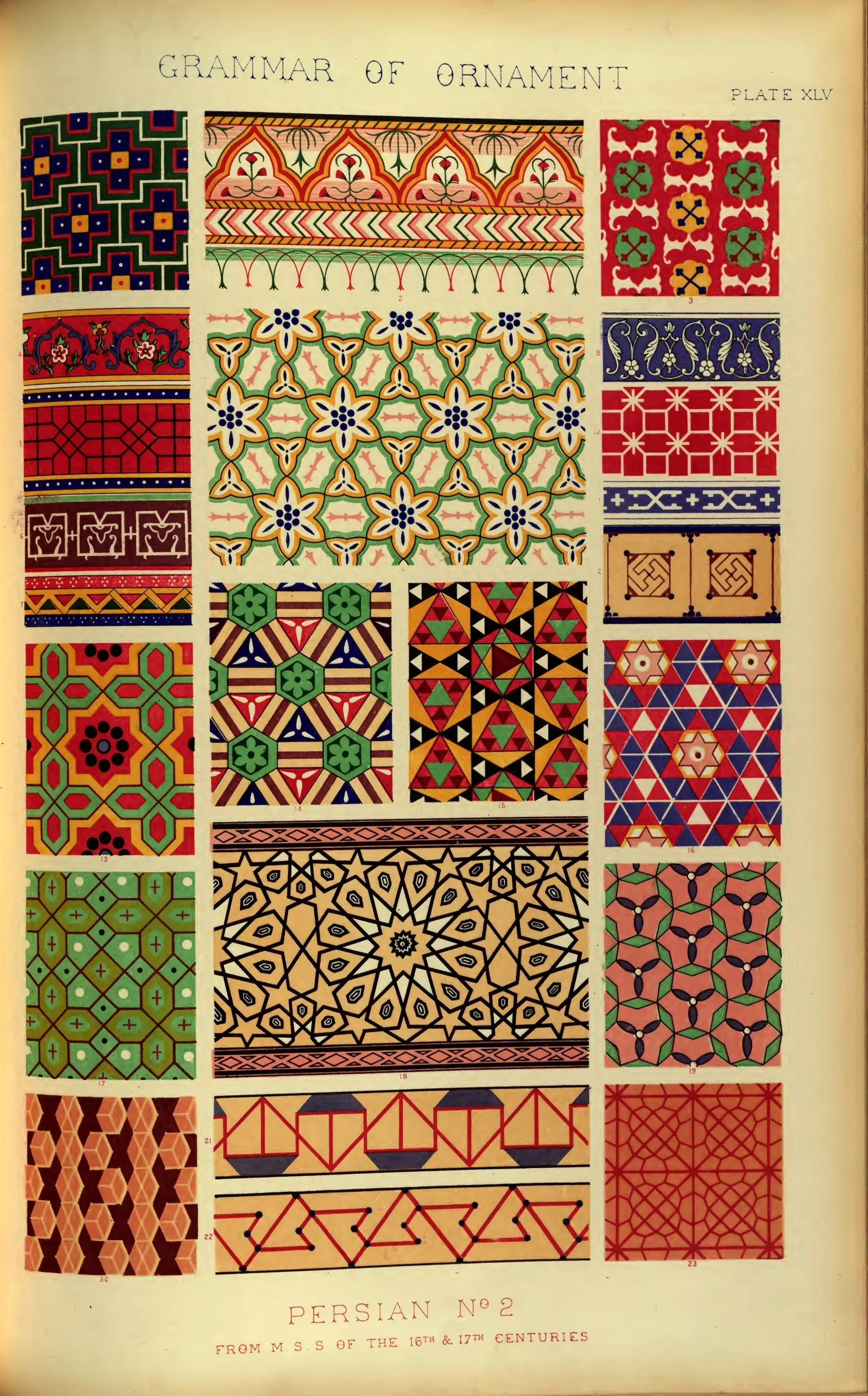

Owen Jones and the Grammar of Ornament

Among the most influential publications of the Reform era was Owen Jones’s Grammar of Ornament (1856). Having studied Islamic and Middle Eastern decoration, Jones became a passionate advocate for flat, abstract, two-dimensional design. He rejected illusionistic depth and naturalistic copying, arguing instead for bold abstraction and clarity. His vivid color plates — from Egyptian to Persian to the Alhambra — provided students with a treasury of models. Together with the Moralists’ embrace of the Gothic (see Design Reform Part I), Jones helped to open an escape route for designers wanting to break out of the Western box of Classicism and endless revival styles.

From The Grammar of Ornament (1856), Jones set out guiding principles:

• Ornament should emphasize flatness, not illusion

• Color should be bold and harmonious, not shaded for depth

• Forms should be abstracted from nature, not copied literally

These rules placed the Islamic and Middle Eastern ornament Ruskin was so fond of at the heart of Victorian Design Reform.

Title Page. The Grammar of Ornament Owen Jones. 1856. Public Domain. Courtesy of Smithsonian Libraries, the Cooper Hewitt.

Plate XLV. Persian Design of the 16th and 17th centuries. The Grammar of Ornament Owen Jones. 1856. Public Domain. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, the Cooper Hewitt.

Christopher Dresser and Industrial Design

Christopher Dresser (1834–1904), often called the first industrial designer, was shaped by the South Kensington System and by Owen Jones’s teaching. Trained in botany and ornament, Dresser believed that design could serve modern industry while retaining honesty and beauty.

He worked widely for ceramic, glass, and metal firms, creating bold, simplified forms that anticipated Modern design. In the 1870s, he traveled to Japan on a government mission to study their design traditions, returning with insights that influenced both industry and education. But he also drew freely on a vast range of non-Classical sources for inspiration, from Mayan design, to Cycladic Greek, to Bronze Age pottery, and more, always filtered through the principles of stylization and abstraction.

These principles placed Dresser at the intersection of art, science, and industry — and pointed directly toward modern design.

Christopher Dresser — often considered the first true industrial designer — articulated a set of principles that guided his approach to modern manufacture:

Stylize forms and ornament

Avoid literal copying of historic motifs; reduce forms to their essential character.Break away from Western historicism

Look to global sources — Japanese, Islamic, Mayan, Cycladic, and more — for new ideas.Cultivate “art knowledge”

Train the eye through the study of fine art and good examples of objects. Design must rest on informed judgment.Honor materials and structure

Let the nature of a material and the logic of construction guide the design.Value design over cost or labor

The worth of an object should not depend on how long it took to make or how much ornament it carries, but on the clarity and integrity of its design.

Pitcher. Christopher Dresser. 1880. Made by Linthorpe Art Pottery (Yorkshire, England, 1879-1889) Public Domain. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago. Accession no: 1987.214

Design Drawing. Christopher Dresser. 1883. Public Domain. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accession no: 1992.1046.12

Conclusion

The Pragmatic Path of Design Reform was about institutions, training, and practical frameworks. It addressed the shortcomings revealed at the Crystal Palace by supplying better models, educational systems, and guidance for industry. While the Moralists—Pugin, Ruskin, and Morris—spoke of ethics and beauty, Cole, Redgrave, Jones, and Dresser offered tools and strategies suited to an industrial age.

Together, they defined the second Path of Victorian design reform: not lofty ideals, but pragmatic structure.

Dresser, in particular, represents Pragmatic Reform at its most effective—bridging art, science, and manufacturing to improve everyday objects for a modern age. Yet in his embrace of the fine arts, his inventive freedom, and his reach beyond the familiar, he also stood with one foot in the third Path of Design Reform: the Aesthetic Movement.

For further reading: Intro to Design Reform Design Reform Part I: Moral/ Idealistic

If you would like to know more about Christopher Dresser, this is a good place to start: The Christopher Dresser Society

Sign up below to be notified about new posts…and more.