Why Art and Design?

Because it represents who I am as an artist — what inspires me and how I approach my work. It describes a state where the poetic meets the practical, and in interior design—as in life, in my opinion—there is no better place to be.

Stock image (Public Domain)

Interior and photo by the author

Stock image (Public Domain)

When art and design are successfully reconciled, the results appeal simultaneously to the heart and mind.

And that is a whole new kind of fulfillment.

Whether it’s the primal pull of Lascaux imagery, the meditative magic of a Malevich black circle, or the brilliant brushwork of a Gainsborough, art makes us feel. That is poetry. Art often summons themes of creative freedom: boundless, spontaneous, emotional. Poetic, yes—but unbridled expression can be overwhelming and chaotic, which is fine, if that’s the artist’s goal. But tempered by the intellect—by “design”—art can be elevated to a more effective level of eloquence.

Detail, Cave Painting, Lascaux. Dordogne, France. c.14,000 BCE. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Black Circle. Kazimir Malevich. 1924. Oil on canvas. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Courtesy of Russian State Museum, St. Petersburgh

Mr. and Mrs. William Hallett (The Morning Walk). Thomas Gainsborough . 1785. Oil on canvas. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Courtesy of the National Gallery, London

Conversely, “design” alone can be quite uninspired—a formula. “Modern” and “timeless” don’t have to mean “boring” or “repetitive.” The degree and quality of artistry, of craft and creativity—of poetry—that infuse design is what makes it moving, meaningful, and unique.

When Art and Design Meet

When Art and Design are brought together with intentionality, Meaning emerges —

and that Meaning is the Concept that guides the work.

But this isn’t magic — it follows a pattern deeply rooted in how the human mind perceives the world. We are wired to seek a balance between freedom and structure, surprise and order. Too much chaos and the mind grows anxious; too much predictability and it goes numb. Psychologists like Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describe this equilibrium as the place where “flow” happens — where challenge and clarity work together to create engagement. A similar principle appears in Gestalt theory and in Gombrich’s writings on perception: the mind delights in variety, but only when held within a unifying structure. (see sidebar)

Design provides that structure — the clarity, order, and purpose our minds crave. Art provides the variation — the emotion, inventiveness, and expressive surprise that make a space come alive.

The Psychology of Meaning

Psychologists have long noted that the human mind thrives in the space between chaos and order: enough structure to feel grounded, enough variation to feel alive. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes this balance as the threshold of flow — the place where challenge and clarity meet and creativity comes alive.

Gestalt theory echoes this idea: we naturally seek patterns, unity, and coherence, yet we also crave variation and surprise. Too much sameness becomes dull; too much freedom becomes overwhelming.

In The Sense of Order, Ernst Gombrich observed that the eye delights in “order enriched by surprise,” a dance between expectation and discovery.

Taken together, these theories reveal something essential about why certain spaces resonate: the mind is most engaged when structure and variation are held in intentional balance. To me, in design, this balance appears as the meeting of Art and Design, the Poetic and the Practical. And when this union is approached with intention, Meaning emerges.

A Life Immersed in Art

Stock photo (Public Domain)

I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t drawing, building, making something, or captivated by something beautiful—a line, a shadow, the curve of a chair. And I feel like I was born knowing who Michelangelo and Picasso were. My father was an artist, but also possessed of that rare mix of the sensitive and the cerebral that had him regaling us with stories and images of great art and artists before we could even read. I learned about Lautrec at seven years old, when he renamed my kitten (Tabby) Toulouse. He taught me, without ever saying so, that art isn’t just a skill; it’s a way of seeing and thinking. Whether nature or nurture, I can’t say, but I definitely have the left-brain/right-brain thing going on.

That attribute guided me into a life that would cross continents and disciplines. I began in studio art and art history, studying painting, sculpture, architecture—visual expressions of the human spirit—while creating works of art at the same time. But I was always more drawn to the tactile and the three-dimensional—to the rooms in the paintings and architecture lectures that no one talked about—the interiors themselves and how furniture and objects activated space.

Discovering Design

Stock photo by Alexander Kagan (Public Domain)

My path to interior design began with a postcard announcing Parsons School of Design’s first summer program in Paris on the history of French furniture and interiors. I was the first person to register—and it changed everything. I discovered that what truly fascinated me was how art becomes environment—how creativity takes form in the spaces we inhabit and the things we use. And that it all means something.

That experience opened the door to a year of immersion in the fine and decorative arts at Christie’s Fine Arts Course in London. One of the best years of my life. Upon returning to the States, I was hired by Christie’s as the registrar for all the fine art departments. I was hoping for an eventual transfer to European Decorative Arts, but instead I was invited to join the Impressionist and Modern Paintings department—a small team handling some of the most important art auctions in the world. And one just doesn’t say no to that.

Later, it felt like a six-year detour; but today, I see it as indispensable. The years spent surrounded by masterworks of progressive, nineteenth- and- twentieth-century art profoundly informed my creative vision and practice as a designer and professor. They also propelled me, six years later, toward a more active creative life.

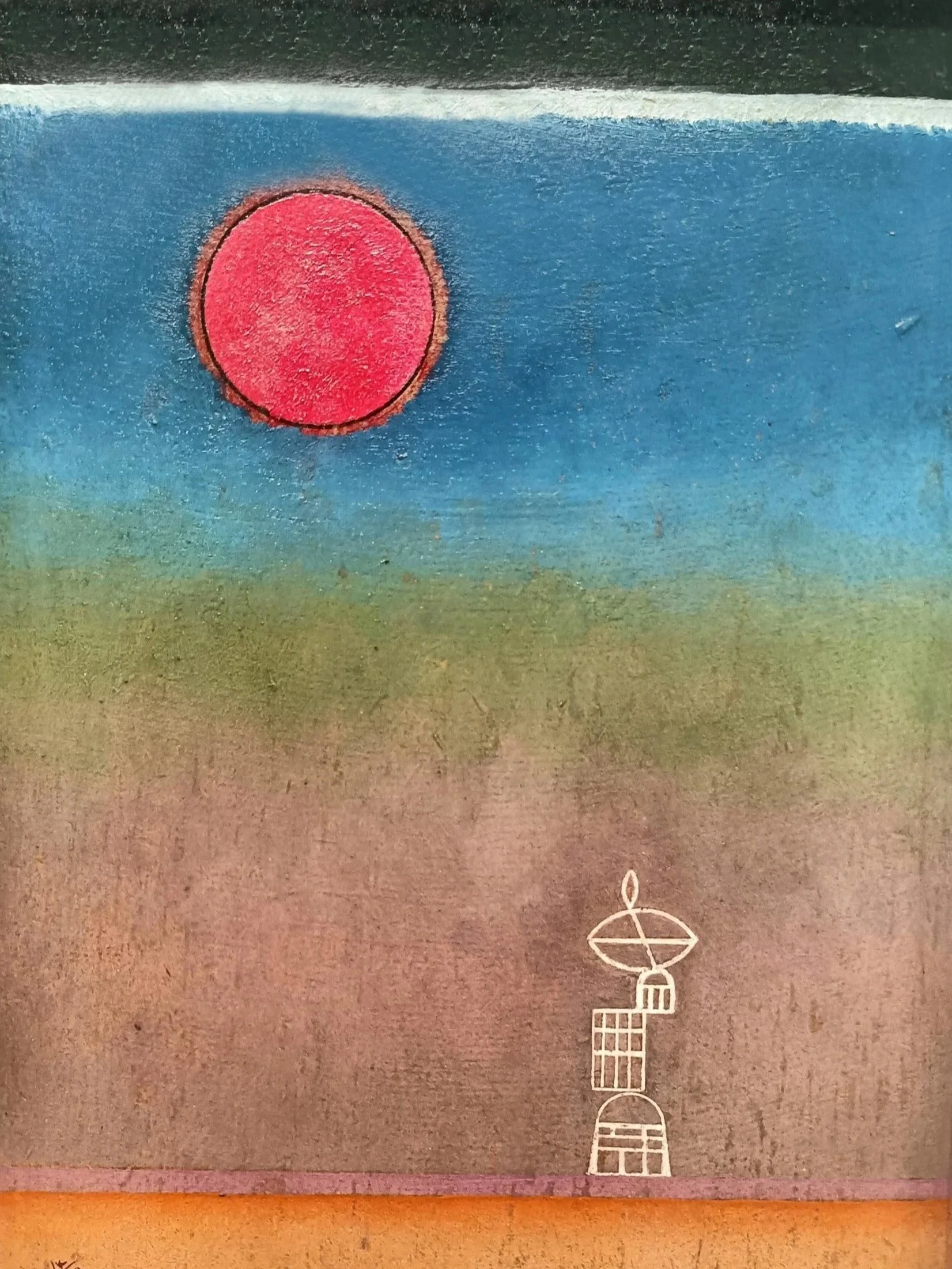

Far Away. Wassily Kandinsky. 1930. Oil on board. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Dancer in Green.” Edgar Degas. c. 1879. Pastel on paper. Public Domain. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

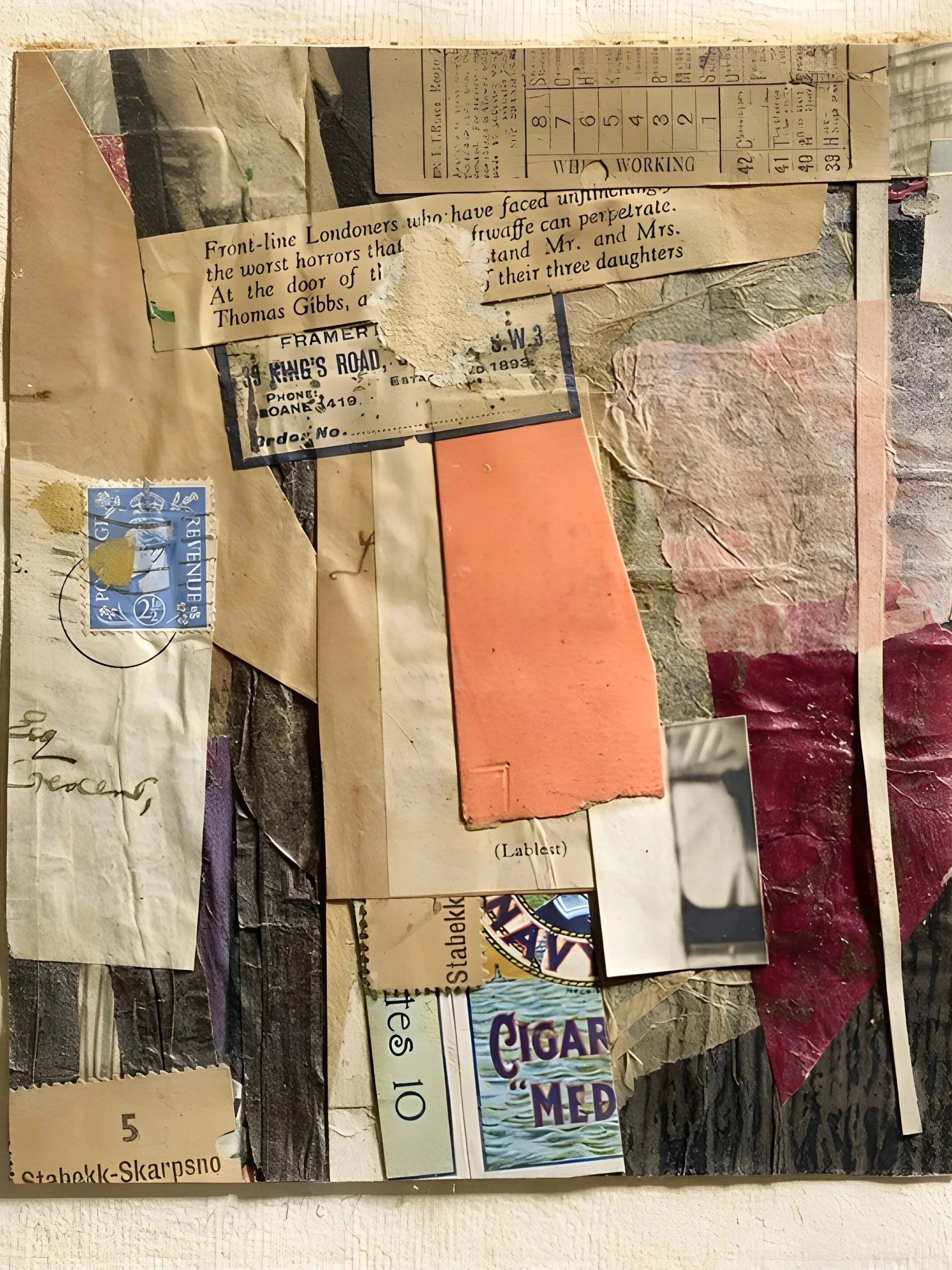

M25. Kurt Schwitters. 1920. Collage. Public Domain. Courtesy of Stiftung / Sprengel Museum, Hanover

You stand there and look at a painting. Then you move on. And it’s over. I needed art in three dimensions; art that becomes part of life. And that’s the beauty of design: it turns aesthetic ideas into daily reality. Which aligned perfectly with my dual nature: the poetic and the practical.

After a year of full-time study at Parsons, I had to return to work. So while gaining experience working a variety of jobs by day—construction management in NYC, small design firms in NJ and NYC—I earned my interior design degree at night from Parsons. That was the poetic education. This was followed by additional courses at the New York School of Interior Design for the practical. Soon enough, I was fully on my own, completing projects in the United States and Europe.

But after years of creative immersion, I began to feel the pull of the intellectual again. So I pursued a long-held dream: earning an MA in the History of Design and the Decorative Arts at the Parsons/Cooper Hewitt program. What I absorbed there, along with a lifetime of exposure to great art, is what imbues my work with the qualities of beauty and authenticity many claim to sense there.

Entry Hall, Naples Florida. Ryan Art & Design. Photo courtesy of Builders Integrity Group

Meaning Became the Heart of My Teaching

After years of study, teaching felt like the most meaningful way to continue the conversation—to explore, question, and share what I had come to understand about art and design.

From the moment I graduated, I was fortunate to teach the history of furniture and interiors at programs in New Jersey, New York City, and Philadelphia. What surprised me most was that students recognized the need to identify styles and memorize periods, but few understood why styles looked the way they did -- what they expressed about the culture of the time; what they communicated; and that they could do the same in their own work.

Eventually, I was invited to teach studio courses -- Elements and Principles of Design and Studio I -- where I find great satisfaction in helping students expand their creativity by connecting the dots between the abundance of inspiration and insight available in art and design history and the projects they are working on.

I don’t just want students to recognize a Chippendale chair or an Early Modern table; I want them to feel the idea behind it, to understand what it meant then, what it means now, and why. To see design as a language of emotion and thought.

Once you understand that, you design differently. You stop decorating and start communicating. That’s why all the courses I teach, whether history or studio, revolve around one principle: how meaning is made.

The Invisible Formula

In truth, my philosophy does involve a kind of formula — but an invisible one.

Art + Design = Meaning

Design gives a project its structure and purpose.

Art gives it expression, emotion, and atmosphere.

Where they meet with intention, a Concept can emerge — the coherent idea behind the work.

When that Concept is fully expressed, the result is Meaning.

This is the moment a space stops being merely attractive and becomes communicative. It has presence. Identity. A point of view.

Conclusion

We live in a fast, visual world—one that scrolls past beauty before it can register and often confuses style with substance. In that environment, I think it’s more important than ever to slow down and ask: What does this mean?

Art and design are our oldest languages. They tell us who we are and how we see the world. They connect the individual act of creation with the collective story of culture.

When students begin to see that connection—when they realize that every design decision carries an emotion, a philosophy, a message—they start to create with purpose. And that’s when their work comes alive.

Conclusion: To Learn, To See, To Create

After years of practice, study, and teaching, I’ve come to believe that art and design are not separate disciplines but one continuous conversation. Art gives us insight; design gives that insight form.

That’s why I teach the way I teach. To help students—and anyone who wants to go deeper—see that beauty is not surface. It’s structure, idea, and intention. To show that when you understand why things look the way they do, you begin to design with authenticity. And to remind us all that in every line, color, and proportion, there is a story.

Epilogue

Of those who say you must choose one or the other—practice or scholarship, the material or the mental—I ask this: What was the foundation of the nineteenth-century Design Reform movement, which led to the emergence of Modernism in the twentieth century? If you don’t know and would like to find out, see my blog post series on Design Reform.

Related Reading: Design Concept in Interior Design

Sign up below to be notified about new posts….and more.