Design Concept in Interior Design: Meaning, Method, and Creative Depth

What is a Design Concept in Interior Design?

A design concept is the “why” behind the “what”

Your concept is your North Star. AI-generated image. @Teresa Ryan, 2025

At its core, a design concept is the unifying idea that drives a project. It’s the intellectual and emotional foundation for every decision. The difference between concept and design is that design is the product of the concept, as expressed through the Elements and Principles of Design. A concept isn’t just a mood board or a style — it’s the deeper logic and meaning behind what a space becomes. Think of it as your north star — a guiding principle that keeps your aesthetic choices and functional requirements in alignment.

Understanding concept starts with learning to see design historically and analytically. To clarify, consider the two questions I tell students in my History of Furniture and Interiors courses they should keep in the front of their minds to help them understand any style they might encounter:

What does it look like? Why does it look like that?

If they can answer these two questions about any style, they can pass the course easily. For every historical style, from Prehistory to Deconstructivism and beyond, looks the way it does for a reason. None developed in a vacuum or on a whim. They arose from forces both deliberate and unconscious; and those forces are what gave rise to the style. Shaped it. Literally.

Those resulting formal qualities become the defining characteristics of the “style;” and the style becomes a physical expression of the meaning of those forces: the concept. Styles are not just interesting artifacts. They are ideas carried through form, function, and feeling. In other words: meaning. And there is no better way to make your work more valuable to your client -- and more creatively satisfying to yourself-- than to endow the project with meaning.

Style tells you what something looks like.

Concept tells you why it looks like that.

A French, Louis XV, Fauteuil à la Reine. Frame by Nicolas-Quinibert Foliot, probably after a design by Pierre Contant d'Ivry. Tapestry woven by Beauvais Workshop director, after designs by Jean-Baptiste Oudry. 1754 -56. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC. 66.60.2. Public Domain.

A French, Louis XVI, Fauteuil à la Reine. Frame by Georges Jacob.Possibly embroidered by Joseph-François-Xavier Baudoin Date: c. 1780–85. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC. 58.75.25. Public Domain.

In many ways, these two chairs are identical. But they are two distinct styles, from different periods. What is it that makes them different? And WHY was that distinction made? What is it saying? What does it mean? The differences between styles illustrate how form expresses meaning – and why understanding concept is essential to design thinking.

Why a Design Concept Matters

A design concept transforms design from decoration into intention.

A strong design concept gives your project clarity and cohesion. It:

- Helps you make the best decisions about every aspect of it, without agonizing or uncertainty

- Makes the project more creative

- Creates meaning

All of which enhance your satisfaction with your work and your standing as a professional. For concept is what elevates design from decoration to intention. It’s what separates a cohesive, meaningful space from one that’s just a collection of attractive features. Whether you’re developing your first student project or refining a presentation, understanding the design concept — and how to develop it — is the starting point for eloquent, evocative design.

Elevation of an Interior in a Parisian Residence. By the sculptor and ébéniste, Alexandre Charpentier. 1900-01. Musée d’Orsay. OAP 240. Image @Teresa Ryan, 2025 Every line, shape, form, and material was chosen for what it means, with the resulting whole communicating the Art Nouveau philosophy about design.

Two Main Types of Concept

Before going through the process for developing a concept, it’s important to know that there can be two different kinds of design concept.

Type A: Relates directly to the client, to the program, or to the location of the project. Example: A boutique hotel inspired by its coastal site

Type B: Independent of client.

(i) more personal to the designer Example: A “minimal” or “traditional” concept

(ii) more universal Example: A “nature-based” or “timelessness”

In my opinion, Type A is where you have the opportunity to be more creative; and it’s an easy sell, for it makes the project meaningful to the client. Most appreciate that self-centered focus. If the project is a business, you would have considered their brand identity; you would have read their Mission Statement, where they explain in their own carefully chosen words exactly who they are; what their values are. You would have spoken with employees and executives to understand function, culture, and history.

Through your research, you may develop some new insights, connections– concepts --that compliment or enhance their identity. The concept can also be connected to the geographic location of the business, if that is meaningful to the client and their brand. So, a concept can have more than one source. But not too many, or all meaning will be lost.

For residential projects, through the programming process, you would have learned what matters to the clients on a superficial level. What would their Mission Statement sound like if they wrote one? But you would also have tried to uncover the essence of who these people are. And the research you conduct would yield creative and meaningful connections between the important aspects of their lives that can be integrated into the project.

If your concept is Type B – unrelated to the project itself – it might be one of two kinds:

i. more personal to you, or…

ii. something more universal

An example of (i) would be if you are a designer with a signature style that reflects your beliefs, philosophy, etc., and clients come to you for that “look,” that “concept.” Or it may arise from your own interests at the time, or experiences, or a design approach you’ve been thinking about -- “traditional maximalism,” for example, which actually has several layers of meaning. The sources are infinite. Even “trendy” themes can be concepts. Think “Coastal” and “Modern Farmhouse.”

A good example from Design History of a personal design concept is Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Prairie Style.” Very simply stated, this developed from his belief that architecture should be connected to the geography of the location. Specifically, they should express the long, low, prominent horizon line of the Mid-West. This “concept” gave rise to a signature style/ look/ aesthetic: houses that are long and low.

Frederick C. Robie House. Chicago, Ill. Frank Lloyd Wright. 1908. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The (ii) type of concept – universal -- might be something like “nature.” An evergreen theme, but also with different and ever-evolving approaches. Some other examples of universal themes that can serve as concepts: unity, timeless, geometry, abstraction, nostalgia. The possibilities are infinite.

An example of a transitional style living room. Ryan Art & Design. Naples, Florida. Image courtesy of Builders Integrity Group, Naples, FL.

But beware of these two potential issues:

1. If you decide on a concept that is merely a “trend,” you should have a very good reason for doing it, besides the fact that it’s just “popular” at the moment. And be sure it doesn’t conflict logically with any other aspect of the project. For example, would you do a Modern Farmhouse in a contemporary New York high-rise? If the client really wanted that, it would be your job to educate them as to why that is not a good idea. In fact.

2. If your concept is personal to you, or more universal,it may not resonate with the client. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t take the risk if you feel strongly about it. Part of your job as an artist is to take risks; and part of your job as a designer is to expose clients to new ideas, to elevate their thinking – and the project – to a new level, beyond what is familiar to them. Indeed, that is exactly what many pay you for.

How to Develop a Design Concept

Once you understand the two main types of concept, you can begin developing your own through a structured process.

The Practical Questions: Who, What, When, Where

At the start of a project, there is much practical information that must be compiled. The Who, What, When, and Where of it. Who, When, and Where are fairly straightforward. Who are the clients (personally); When do they want to do the project (schedule); and Where is it located (part of house, geographically).

“What,” however, is more complicated. It poses two questions: one straightforward; one….not so much. The former: What are the requirements of the project? What do the clients need? Simple enough. But the other goes right to the heart of the practice: “What will it/ should it look like?” Which leads directly to the most important question of all: Why? Because…

You cannot answer “What should it look like” until you have the answer to “Why” it should look like that.

Many students, and even some professional designers, struggle with the concept of design concept. If you are one of those, this article is meant to help. As a designer, art and design historian, and interior design educator for over ten years, this is my way of explaining it. Others you encounter may have different ideas, and that’s fine. It’s a highly creative process, so impossible to nail down with one definition or procedure. And it can change from project to project.

Most concepts emerge from a process of research, exploration, and synthesis.

Some General Steppingstones for Developing a Design Concept

(Note: The following steps may seem to apply more to Type A than Type B, but they can also be part of B, especially if it is a new idea, or you want to uncover connections between a pre-existing concept and the project).

Understand the project: During the programming phase, you will probably begin to have ideas about a possible concept.

Brainstorm: what academics like to refer to as “ideation.” Expanding upon those musings that arose during programming. Imagining; writing down ideas; creating quick sketches that express those ideas. But if you want to expand your creativity, you can’t stop there.

Research: is next, the extent and nature of which is up to you. How large and important is the project? How familiar are you with the requirements? How much of your curiosity has been ignited? How excited are you about where this could go? Or how clueless do you feel about what to do with it?

It could be an evening on the internet or two weeks in Europe.Browsing through various products and materials can also be valuable research. For example, on one occasion when I was unsure of the concept, discovering a particular light fixture suddenly brought it all together.The point is, you want to see how much you can develop your initial ideas, uncover new ones, or make connections capable of significantly enhancing the meaning of the project.

Make connections: Do you know that one of the definitions of creativity is finding connections between seemingly unrelated things? (topics, ideas, elements, materials, etc.) By going that extra mile –engaging in “research,” you opened the door to a new level of creative possibility. What is a connection and how do you know if you’ve made one? As this is a highly creative process, it’s hard to describe. But to give you something to go on, here are two possible scenarios:

It might just “happen.” You see something that strikes you as “meaningful” in the context of this project. Then you start musing about why it does and if/how/where it might fit into the project. OR, you see something you think is “powerful” in some way and start musing about if/how/where it might fit into the project.

AI-generated image @ Teresa Ryan, 2025 One of the definitions of creativity is finding connections between seemingly unrelated things.

5. Find the tone of your concept. Create a list of adjectives. No matter what the concept is, there will usually be emotion attached to it. Even if there doesn’t seem to be, dig for it. List as many descriptive words or short phrases as you can that describe the emotion, the feeling, the vibe, that would emanate from your concept. Narrow that down to one or two key words that you think best capture it.

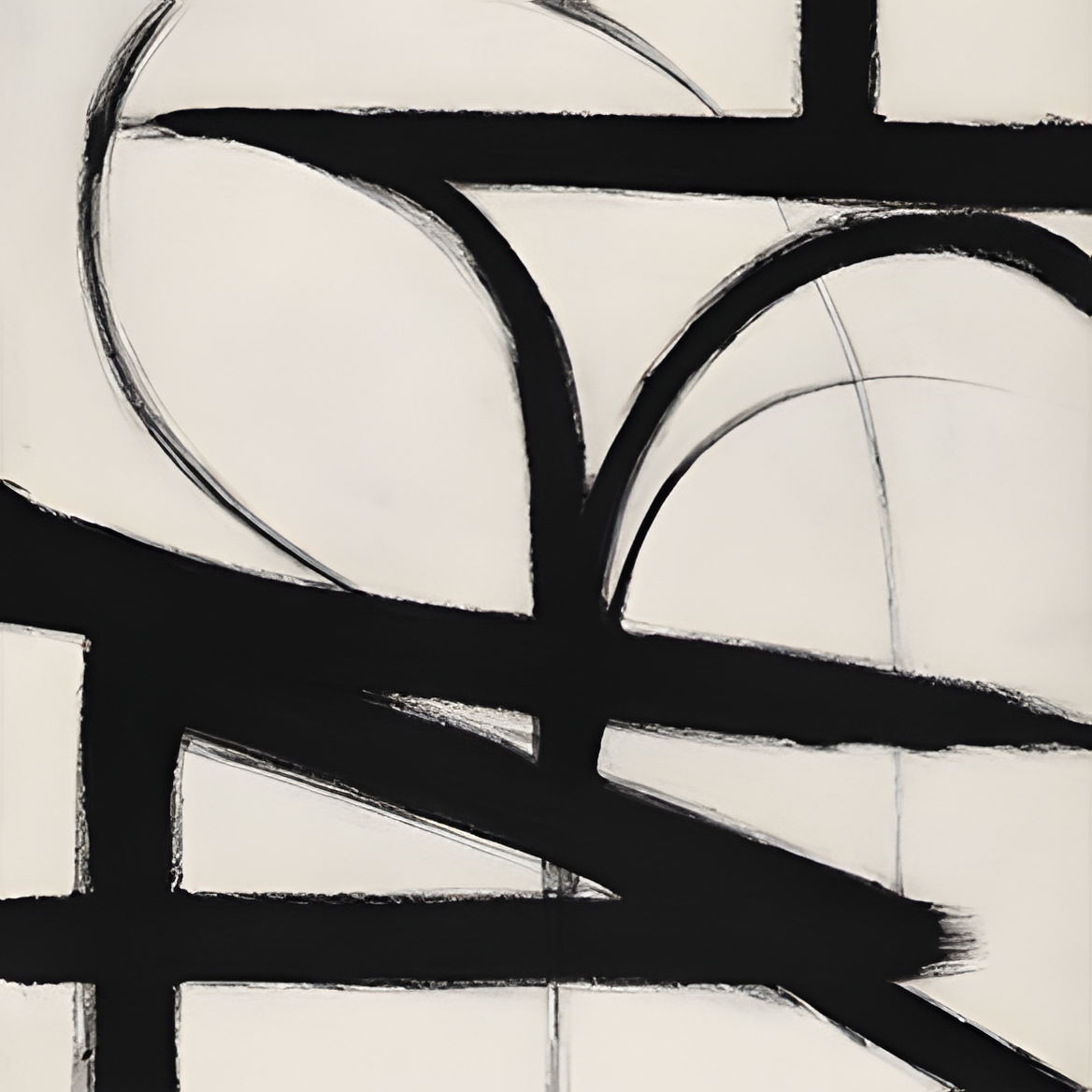

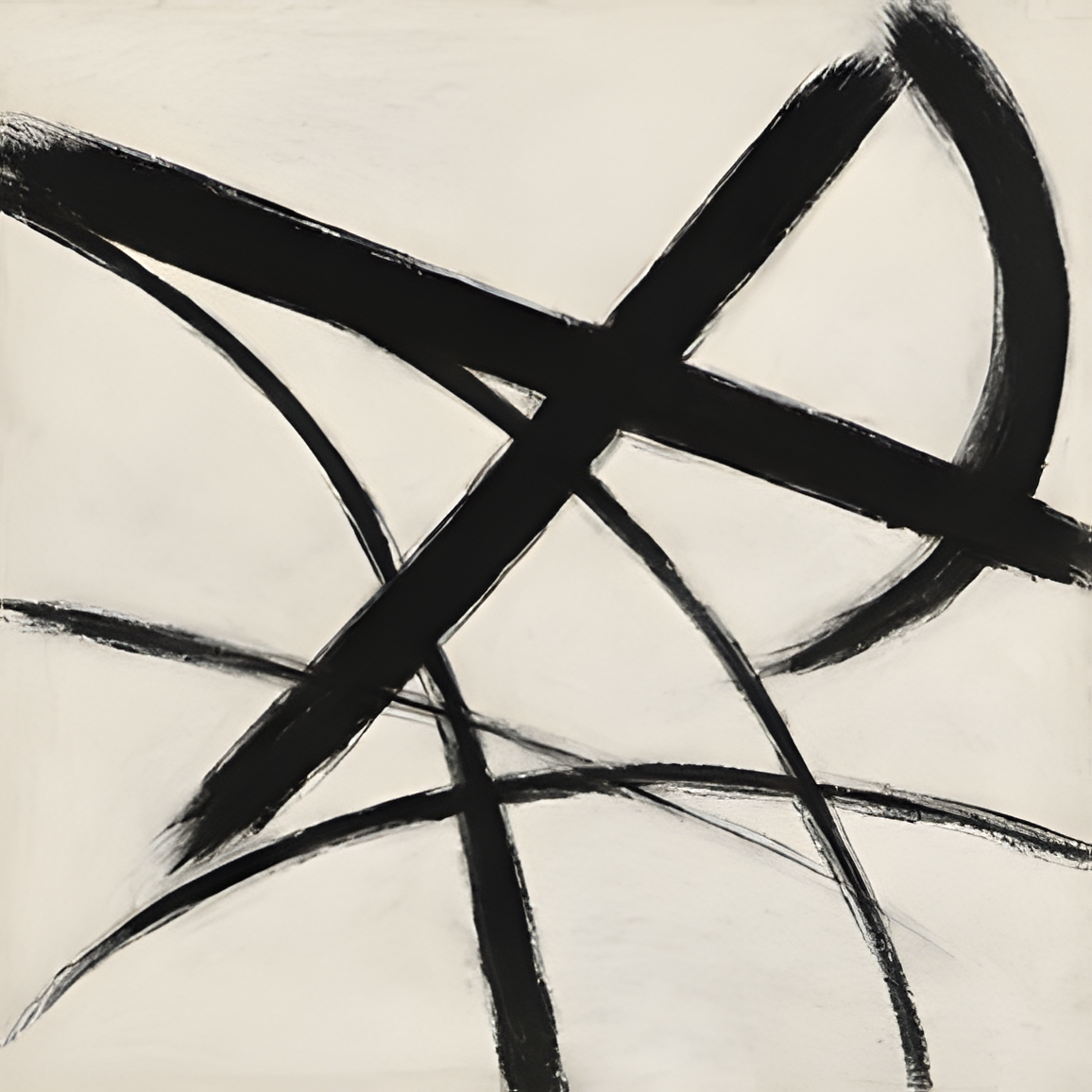

6. Test your concept: The Black and White Test. Grab a large piece of paper and a fat Sharpie, or soft pencil, or black pastel. With broad strokes, try to create an abstract composition that expresses the feeling of your concept word; that illustrates your concept word(s) – through the quality of line, shapes, proportion and scale, contrast. The idea is to see how easy or difficult it would be to translate this concept into materiality.

The goal is to discover the emotional DNA of your project — what it feels like before it takes physical form.

The concept should be able to be expressed in black and white.

Concept is different than “mood,” as you would show in a mood board. They are often related, but they don’t have to be. While colors, textures, and materials can play a big part in expressing concept, the concept should be able to be expressed in black and white through the use of the certain key Elements and Principles of Design. It’s about “meaning” more than mood.

After my Studio I students have completed the Programming phases, but before they start “designing” anything at all, I have them do this exercise: Work on a list of adjectives that capture the feeling(s) you’re having about the project. What they think the “essence” of it might be. Then to refine that list into one or two of the best words. Then express those feelings/ ideas/ concepts in free-flowing, abstract, black and white drawing. Really just relax, let go, pretend you’re in kindergarten, and draw on big pieces of white paper with big black markers.

Where Art and Design Meet

A concept is more than a mood or a stylistic preference. It is the point where design thinking and artistic imagination converge. Design provides structure — the functional requirements, spatial logic, and practical constraints that shape the project. Art provides expression — the emotion, metaphor, atmosphere, and interpretive lens that give it life.

When these two forces meet, a concept emerges:

a single guiding idea that gives a project coherence and purpose.

A concept is not color.

It is not style.

It is the underlying idea expressed through the Elements and Principles of Design — line, rhythm, contrast, scale, balance, unity.

Because it merges clarity with creativity, a strong concept naturally gives rise to something deeper than visual appeal. It creates meaning: a sense that the space has a purpose, a presence, and an identity that resonates.

Concept unites Art and Design; Meaning is the resonance that follows.

Those images could look something like these, but there are no rules. I put myself through this exercise with two key words – concepts – I picked at random. Resilience and Clearing. There are some important passages in each that capture the concept for me, but I would play around with them. Edit them. See where else they take me. Or start fresh. But I wouldl keep all for future reference. Do you see how drawings like this can be a tremendous help starting or developing an innovative—meaningful – space plan?

Abstract Composition, “Resilience” AI-generated image, @Teresa Ryan, 2025

Abstract Composition,”Clearing” AI-generated image, @Teresa Ryan, 2025

For practice, you can “back into” abstract images. Look at abstract works of art. Franz Kline is a perfect place to start. How do those paintings make you feel? What adjectives best describe that feeling? The end result of all this, of course, is that…

….once you have been able to ID lines, shapes, forms, etc

(in other words, Elements and Principles)

that communicate the feeling you want,

you look for – or use -- those same qualities in the things you

choose or create for your project.

Concept and Mood: The Cake and The Icing

A common error is confusing or conflating concept and mood. A helpful example to clarify the difference is the ocean as a concept. The ocean is an idea unto itself, but it can have many different moods: calm and soothing, or rough and dangerous. Turquoise blue and clear, or black and impenetrable. Understand?

You can also think of it as a two-part construct: the practical and the aesthetic. The foundation and the surface. The “cake” and the “icing.” The concept-- being the practical, the foundation, the “cake” -- is about the SHAPE of the essentials. One layer is the interior architecture, floor plan, walls, ceilings, rooms. A second layer might be the shapes of major items of furniture and their placement.

Simply put, the two layers together define the COMPOSITION OF THE SPACE, i.e. the “space plan,” which is the foundation of the design project, and which can be expressed in black and white.

Cake. AI-generated image, @Teresa Ryan, 2025

Cake. AI-generated image, @Teresa Ryan, 2025

When “done,” the “cake” is enhanced by the “icing.” The colors, materials, textures – which create the mood. These are often connected to the concept, but they don’t have to be. For example, “geometry” can be the underlying concept (cake), but the mood (icing) can be somber/ meditative/ intellectual (the all-chocolate) shades of black, white, gray, beige; or colorful/exuberant/playful, as in a child’s playroom, like the rainbow icing.

When concept and mood work in harmony, the result is design that feels inevitable — both logical and alive.

A strong design concept gives your work depth, discipline, and distinction. It grounds your creativity in purpose and allows beauty to emerge with intention. Whether you're a student grappling with your first studio brief or a professional pitching a high-stakes project, a clear concept is your most powerful tool.

Entrance Hall. Princeton NJ. Ryan Art & Design. Image @Teresa Ryan, 2025

A Christopher Farr carpet based on a design by Gunta Stolz, the Bauhaus, c. 1920, for an early 20th-century, American, Arts and Crafts style house is meaningful on several levels: the relationship between Design Reform, Arts & Crafts, and Modernism; the amusing play on the numerous recessed millwork panels; and its contribution to the fun and quirky vibe the client wanted.

In my opinion, the most successful concept is something essential about the client you have isolated, and which they greatly appreciate, expressed through your own personal style of creativity, your own identity. (There it s again. That reconciliation of opposites. A and B. Client and You. See Why Art & Design?). For no matter the concept, you are best able to elevate the project by bringing your creative, personal “self” to it – which is, in any event, unavoidable.

“Who You Are” will always come through,

and that alone will make the project a unique work of art.

Conclusion: Design with a Reason for Being

The design concept is your true north, the idea that keeps every decision aligned with meaning. When you design with a concept, beauty follows purpose, and your work becomes more than decoration: it becomes design with a reason for being.

Related Reading: The Elements and Principles of Design Why Art & Design?

Want to test your concept? Download the worksheet and start your next project with meaning.

Want to go deeper? Sign up here to be notified about new posts…and more!